|

|

THE SAFETY VALVE |

|

"I’ve always been kind of a Don Quixote, and I saw this as an opportunity to realize that." Pix Howell was overlooking the pool house of one of the new subdivisions sprouting up around Austin like cedar. Howell may not have developed any of the Belterras, Sweetwaters, or Bella Vitas blanketing the hillsides that once held little more than goat ranches, but he holds claim to them as much as anyone. After all, he brought the water.

Back in the 1990s, the rocky hollows of Hays and West Travis County were being plowed under and replaced with acres of 4 bedroom homes. Each new development was a taproot burrowed into the Edwards or the Trinity Aquifers, and the pumping was taking its toll. The Dripping Springs that gave its name to the seat of government in Hays County no longer dripped; even reliable wells were producing far less than they ever had.

Back in the 1990s, the rocky hollows of Hays and West Travis County were being plowed under and replaced with acres of 4 bedroom homes. Each new development was a taproot burrowed into the Edwards or the Trinity Aquifers, and the pumping was taking its toll. The Dripping Springs that gave its name to the seat of government in Hays County no longer dripped; even reliable wells were producing far less than they ever had.

|

“I really think that the use of meaningful transmission pipelines in Central Texas—and I’m really thinking about a grid—makes it possible to balance the use of the resources.”

--Pix Howell |

At the time, Howell was a board member of the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA), which provides water to Austin and the recreation and retirement communities of the Highland Lakes. He had settled his family in Dripping Springs in the eighties. The Hill Country was the only place in Texas he wanted to live, a sentiment he knew was shared by many of the thousands flooding into the state every month, and summed up in the words of a billboard advertising one of the Hill Country subdivisions that Howell had planned: "If you're thinking of living in Pflugerville, why'd you ever leave Lubbock?"

The only thing that stood in the way of the growth machine of the Texas Hill Country, Howell believed, was water. Opponents of growth had for years resisted the extension of new infrastructure west of Austin. The LCRA wasn't in the business of soliciting new water customers; 90% of their revenue came from power sales, but it felt like 90% of the work went into managing the water they sold on the cheap. But Howell was convinced that the future of Hays and West Travis Counties depended on the water of the Highland Lakes, and in what he regards as a quixotic victory, he negotiated the extension of a water pipeline financed by the LCRA. “The idea,” Howell says, “was generally to furnish water necessary, if for nothing else than the growth that was already there.” |

The LCRA lines did much more than provide for existing development: from 2000-2010, Hays County’s population grew by another 60%. But that, said Howell as we overlooked the pool, doesn't mean the water is there to serve it. “Central Texans all have done a great job of trying to get ahead of transportation. Not that they have,” Powell says, “I don’t think we’ll ever build roads big enough as long as we have a commuter based system. But with that, those bonds that have been sold to build those roads depended on a demographic that just assumed that growth would have water available to it, and what is becoming more and more apparent is that that is probably not the case, that those demographic projections just made that assumption without any actual basis.”

More water must be found, Howell decided, and in 2013, he brought a deal to the Hays County Commissioners Court. For $1 million a year, the county could reserve an option for water in the Carrizo Aquifer, 50 miles east in Bastrop and Lee Counties. The contract would give Hays County right of first refusal for water to be developed by Forestar, one of any number of companies signing water leasing arrangements with landowners around the state.

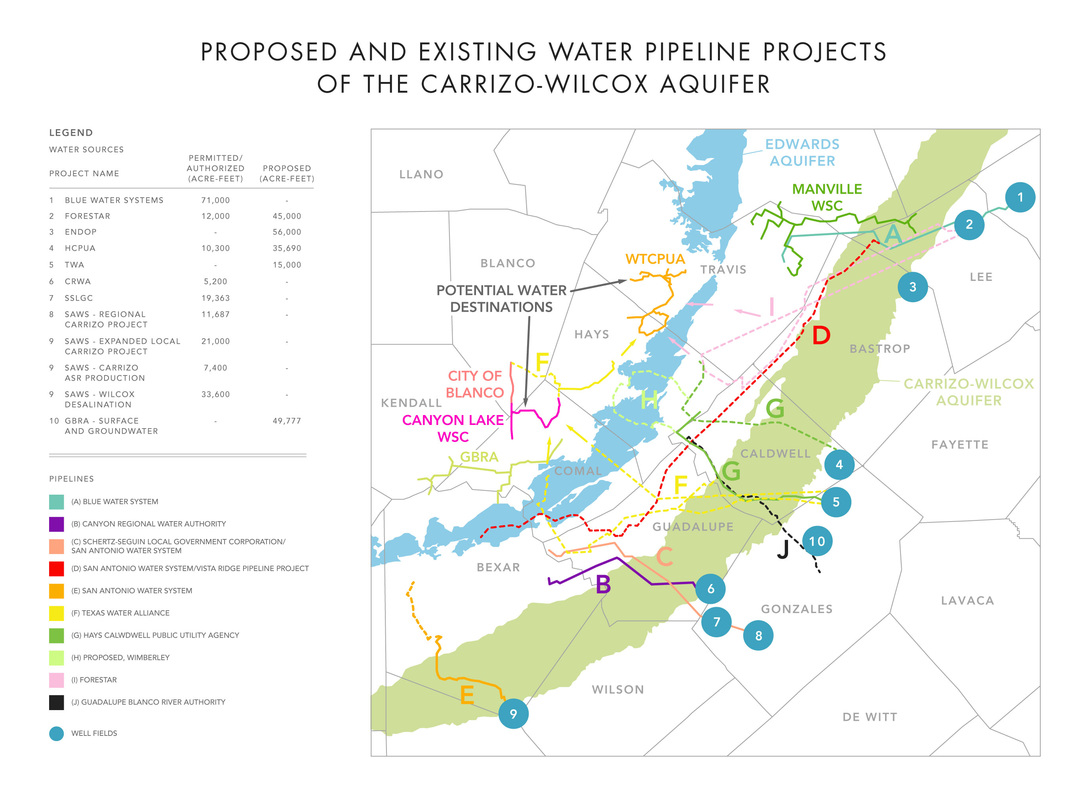

The Forestar project was one of nearly a dozen planned or existing pipelines from the Carrizo Aquifer to the megalopolis of Austin-San Antonio. The Carrizo extends from the Mexican border, across the gas-rich region of the Eagle Ford Shale, up through the pasturelands near College Station, reaching all the way to the Louisiana border, a rich deposit of water cradling the high-growth regions of Central Texas.

More water must be found, Howell decided, and in 2013, he brought a deal to the Hays County Commissioners Court. For $1 million a year, the county could reserve an option for water in the Carrizo Aquifer, 50 miles east in Bastrop and Lee Counties. The contract would give Hays County right of first refusal for water to be developed by Forestar, one of any number of companies signing water leasing arrangements with landowners around the state.

The Forestar project was one of nearly a dozen planned or existing pipelines from the Carrizo Aquifer to the megalopolis of Austin-San Antonio. The Carrizo extends from the Mexican border, across the gas-rich region of the Eagle Ford Shale, up through the pasturelands near College Station, reaching all the way to the Louisiana border, a rich deposit of water cradling the high-growth regions of Central Texas.

|

"Those bonds that have been sold to build those roads depended on a demographic that just assumed that growth would have water available to it, and what is becoming more and more apparent is that that is probably not the case."

--Pix Howell |

“I really think that the use of meaningful transmission pipelines in Central Texas—and I’m really thinking about a grid—makes it possible to balance the use of the resources,” Howell told me in the fall of 2014. “Because you may always use Trinity water, you may always use Edwards water, you may always use Carrizo water, for that matter, Colorado [River] water if it ever rains again. The capability to be able to balance that is the most critical item that everybody needs to be wrassling with right now.”

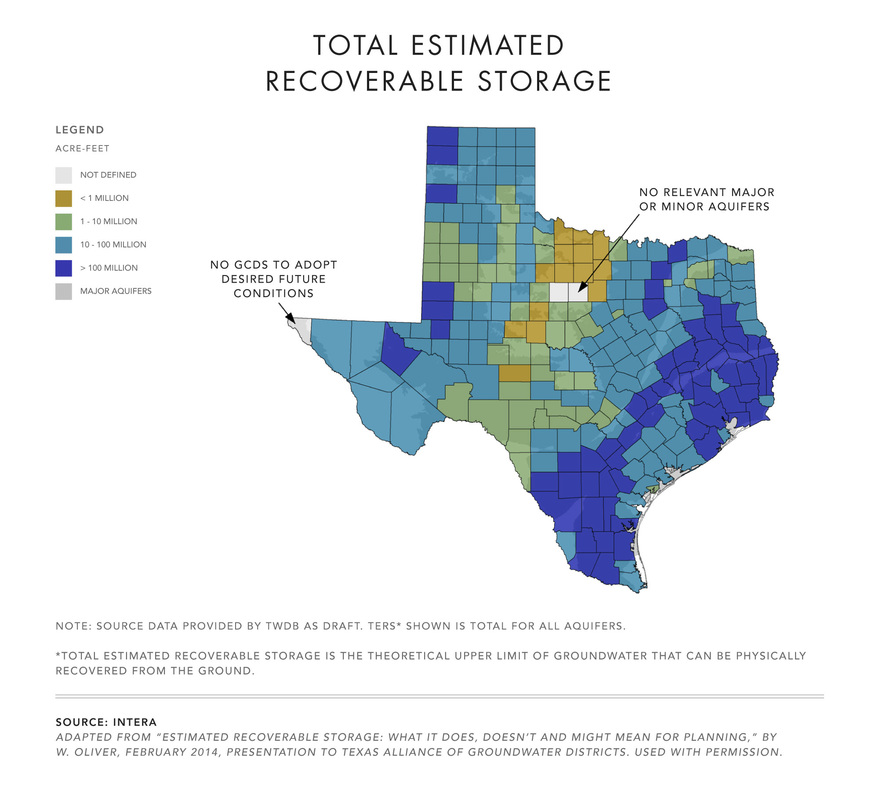

The idea of a water grid connecting less developed areas of the state like the Carrizo to high-growth regions took off in the 2015 Legislature, partly buoyed by the notion that interconnecting water resources allows us to balance our demand on them. The argument was the same in Hays County, where the Forestar project was promoted as a solution to the persistent groundwater declines in the Trinity Aquifer--declines that, proponents implied, would be reversed if new water were made available. How the aquifer's recovery would be accomplished was never entirely clear--proponents of the pipeline weren't promoting more restrictive groundwater permitting in the Trinity. History certainly wasn't making a strong case for the link between adding new water and restoring groundwater supplies, either: since the LCRA lines were extended into Hays County, groundwater production has quadrupled. In the end, Howell's latest sally to re-engineer water in the Hill Country did not enjoy the success of his first. While the Commissioners Court signed the contract, eventually paying Forestar around $1.5 million over 2 years, the water Forestar promised for Hays County far exceeded the water it was permitted to pump. Forestar filed suit against Bastrop and Lee's Lost Pines Groundwater Conservation District [GCD], claiming it was taking private property from the landowners that had leased their water by restricting how much they could sell. (source) That case is still pending, but Hays County is no longer part of the deal--in the eyes of some, one more victim of the territorial nature of local control. “We have to start thinking regionally instead of always trying to be in control of the resource,” says Howell. “What’s occurred instead is that some districts have taken this on more as, I guess you’d say, as a political issue, more of a protectionist issue.” For Howell, as for other advocates of interconnecting Texas’ water resources, water shortages are an artificial condition created by territoriality over local supplies—shortages that would be solved, if only other regions would share their water surplus. As evidence of the abundance of water wasting away in the Carrizo and other less-developed aquifers, advocates for amplified production point to the infinitesimal percentage of total aquifer storage that groundwater districts have permitted for production. As evidence, they point to the Total Estimated Recoverable Storage (TERS) of each of the state’s major aquifers, a theoretical estimate of the water that can be physically recovered from the ground. Statewide, this estimated storage tallies up to a staggering amount of water, nearly 16.9 billion acre-feet—slightly less than the total combined storage of the Great Lakes. With that much water underground, the argument goes, the amount of production allowed by groundwater districts is absurdly restrictive—as little as .02% of the theoretically recoverable volume in any given year. |

Howell is one of those who argue that local control of groundwater is failing to meet the needs of Texas in the 21st Century. “The mantra seems to be local control, but in terms of water, it really needs to be regional control. As long as you have the river basins as planning regions for surface water, and this patchwork quilt of GCDs for groundwater, the whole concept of really being able to balance a resource becomes very difficult.”

The Legislature seems to agree. For while local control remains the dogma of Texas groundwater policy, the Legislature has shown itself entirely willing to wrest authority from local groundwater districts to advance the cause of groundwater production.

The Legislature seems to agree. For while local control remains the dogma of Texas groundwater policy, the Legislature has shown itself entirely willing to wrest authority from local groundwater districts to advance the cause of groundwater production.

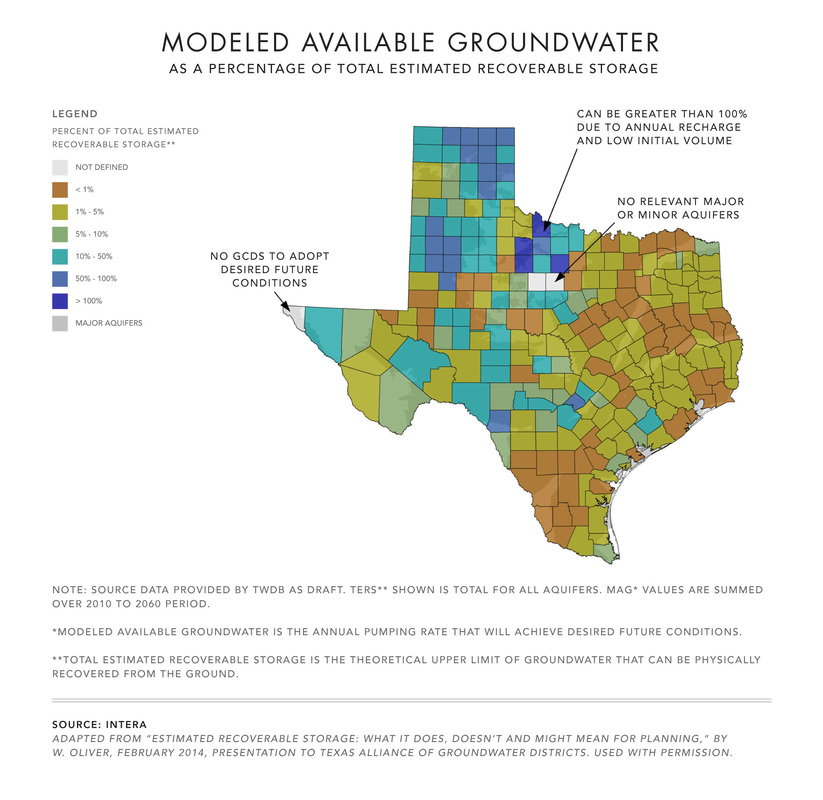

The image on the left represents the total amount of water that is theoretically recoverable from Texas' aquifers, represented at the county level. The image on the right shows the amount of water that groundwater districts will allow for production over a 50 year period as a percentage of the total estimated recoverable storage. This infinitesimal percentage is used by some groundwater production advocates as justification for maximizing the permitting of groundwater production. But estimated storage doesn't capture the whole story of how groundwater use can affect availability.

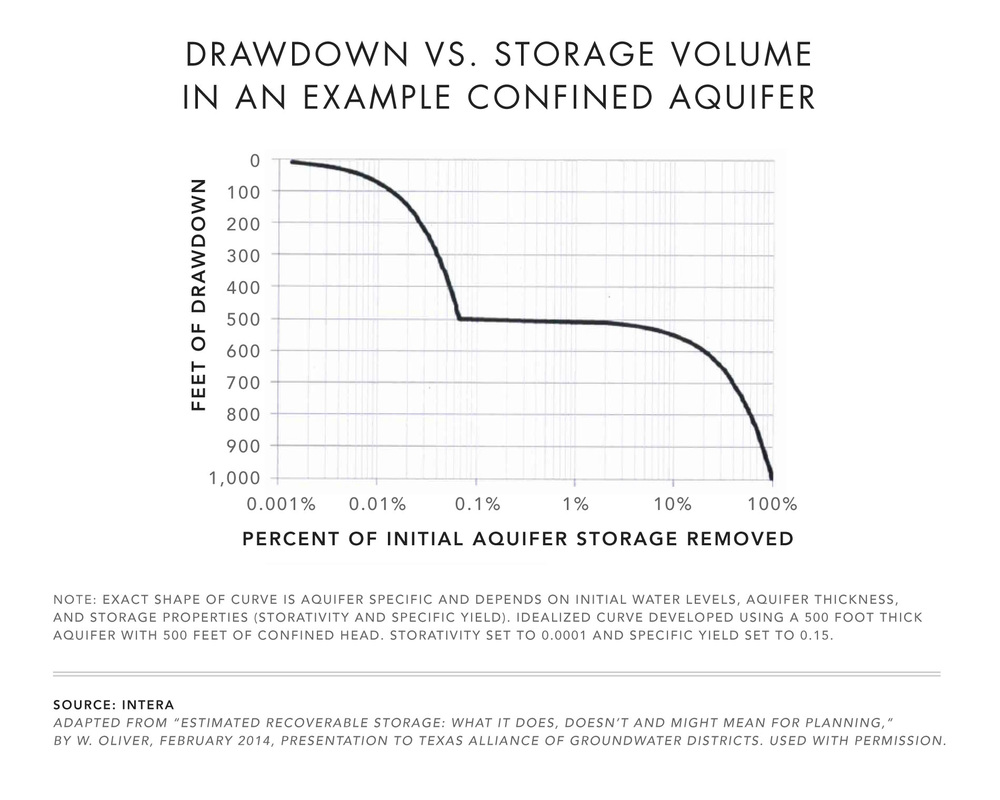

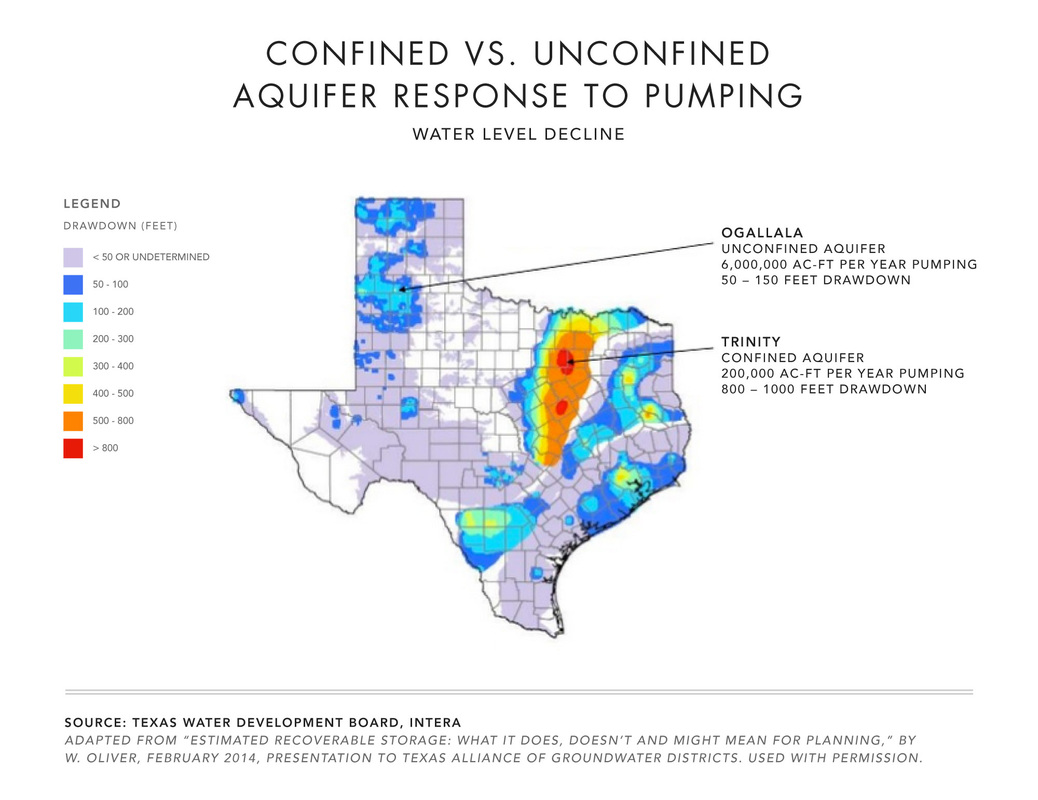

The image on the left shows how dramatically water pressure can decline for aquifers like the Carrizo with only a tiny decline in total storage; increase the amount of water pumped from the aquifer from 0.01% to 0.1% and a theoretical well would need to be lowered by 400 feet to find water. In the zones where the aquifer is depressurized, no water may be found at any depth. In the image on the right, we see how confined aquifers like the Carrizo and the Trinity respond to pumping--less water has been pumped out of the Trinity than is proposed for the Carrizo, yet well levels in the Trinity have declined by as much as 1,000 feet.

In the lead up to the 2015 Legislature, the House Natural Resources Committee released an interim report on groundwater production. "What was once used namely in times of emergency," the report began, "is fast becoming the preferred method for water supply in this state."

The growing interest in groundwater export from rural to populous regions was creating tensions across the state, the Committee found. Groundwater districts, empowered by the Legislature under the banner of local control, were seeking to restrict production in the protection of local interests, while groundwater marketers intent on scaling up production argued that districts "need to understand that the state needs and intends to use groundwater to meet long-term demands state-wide."

Ultimately, the Committee concluded, the Legislature should "encourage groundwater conservation districts to maximize permitting of groundwater resources, whether for in-district or out-of-district purposes." (source)

In the end, the encouragement the 2015 Legislature provided to groundwater districts was to attempt to bypass them entirely, plucking from local control two types of authority. First, the Legislature transferred the power to permit aquifer storage and recovery projects (which store water originating from another source in an aquifer for later use) to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which regulates the surface waters of the state. Then in HB30, it laid the groundwork for what, in time, may be a much greater coup: directing the state to designate brackish groundwater production zones that (based upon the bill's original language) presumably would be beyond the permitting authority of groundwater districts. As defined in the bill, brackish groundwater is any resource with greater than 1,000 milligrams per liter total dissolved solids. That encompasses nearly all of the groundwater of West Texas, and most of the untapped supplies of the rest of the state.

The growing interest in groundwater export from rural to populous regions was creating tensions across the state, the Committee found. Groundwater districts, empowered by the Legislature under the banner of local control, were seeking to restrict production in the protection of local interests, while groundwater marketers intent on scaling up production argued that districts "need to understand that the state needs and intends to use groundwater to meet long-term demands state-wide."

Ultimately, the Committee concluded, the Legislature should "encourage groundwater conservation districts to maximize permitting of groundwater resources, whether for in-district or out-of-district purposes." (source)

In the end, the encouragement the 2015 Legislature provided to groundwater districts was to attempt to bypass them entirely, plucking from local control two types of authority. First, the Legislature transferred the power to permit aquifer storage and recovery projects (which store water originating from another source in an aquifer for later use) to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which regulates the surface waters of the state. Then in HB30, it laid the groundwork for what, in time, may be a much greater coup: directing the state to designate brackish groundwater production zones that (based upon the bill's original language) presumably would be beyond the permitting authority of groundwater districts. As defined in the bill, brackish groundwater is any resource with greater than 1,000 milligrams per liter total dissolved solids. That encompasses nearly all of the groundwater of West Texas, and most of the untapped supplies of the rest of the state.

|

The Legislature's most recent move is only its latest about-face on whether it should be locals or the state apparatus that controls groundwater. Senate Bill 1, which reformed statewide water planning in 1997, allowed districts to prohibit the export of groundwater beyond district lines. Dozens of groundwater districts were created in the following Legislative session in 1999. Then, just two years later, Senate Bill 2 reversed course, prohibiting groundwater districts from denying permits based upon whether the water would be piped away.

|

Who is tilting at windmills, the people who think we can solve our groundwater problem by pumping somewhere else, or those who believe that local control is actually protecting Texas' groundwater?

|

Yet it is hard to argue that the architecture of local control has done much more than permit groundwater production that would be taking place anyway. Groundwater districts may now cover most of the state, but with the exception of the Edwards, every major aquifer in the state is being managed for depletion. In most places, the Modeled Available Groundwater that guides permitting reflects the amount of pumping that was taking place before the groundwater district was formed, if not an even greater amount. The only region where groundwater use is projected to decline over time is the Panhandle, and there, only because there won't be any water left to pump. Hays County is a shining example of the gulf between groundwater regulation and resource sustainability--the county has 4 groundwater districts, but the Trinity continues to decline.

Which all begs the question: just who is tilting at windmills, the people who, like Howell, think we can solve our groundwater problem by pumping somewhere else, or those who believe that local control is actually protecting Texas' groundwater?

Which all begs the question: just who is tilting at windmills, the people who, like Howell, think we can solve our groundwater problem by pumping somewhere else, or those who believe that local control is actually protecting Texas' groundwater?

|

|

THE EXCESS WATER DEBATE |

|

The people of Texas have given the Legislature, in article XVI, section 59 of the Texas Constitution, not only the power but the duty to “pass all such laws as may be appropriate” for the conservation, development, and preservation of the State's natural resources, including its groundwater. The Legislature has concluded that local “[g]roundwater conservation districts are the state's preferred method of groundwater management.” Actually, such districts are not just the preferred method of groundwater management, they are the only method presently available. Yet in the fifty years since the Legislature first authorized the creation of groundwater conservation districts, the record in this case shows that only some forty-two such districts have been created, covering a small fraction of the State. Not much groundwater management is going on. -Sipriano v. Great Spring Waters of America, Inc., 1 S.W.3d 75, 80-83 (Tex. 1999).

|

Nearly 20 years after the Supreme Court opined, the question remains: how much groundwater management is actually going on in Texas?

Roughly 60 groundwater districts have been formed since 1999, but it has been mainly a litter of runts. Two-thirds of districts represent a single county, reflecting neither the hydrological boundaries of the aquifers they regulate nor the economy of scale needed to regulate a complex natural resource. In 2013, only 3 of the state's groundwater districts had gross receipts greater than your average Starbucks. (source) That year, a property valued at $200,000 would have paid only $10 to $70 to its local groundwater district—if that district had the authority to levy tax at all. With that amount of money, groundwater districts are meant to drill observation wells to monitor the aquifers they regulate, to model how aquifers might respond to increased pumping or deeper drought, to encourage the conservation of groundwater through education and outreach, and to defend themselves from litigious landowners who want to produce more water than they will permit. |

In 2013, only 3 of the state's groundwater districts had gross receipts greater than your average Starbucks.

|

Like many of the 100 or so groundwater districts that have been created by the Legislature, the Kinney County Groundwater Conservation District is a democratic but somewhat fly-by-night operation.

Lloyd Lee Davis and Peggy Postell, along with their fellow board members, hold the power to decide how much groundwater may be pumped in Kinney County. To understand the consequences of one person’s water use, the board needs at a bare minimum the ability to monitor water conditions across the county, and the science to understand what present day conditions mean about future water availability. The Kinney County GCD board has little of either.

Lloyd Lee Davis and Peggy Postell, along with their fellow board members, hold the power to decide how much groundwater may be pumped in Kinney County. To understand the consequences of one person’s water use, the board needs at a bare minimum the ability to monitor water conditions across the county, and the science to understand what present day conditions mean about future water availability. The Kinney County GCD board has little of either.

|

"With excess water available to us, maybe that water could be used elsewhere more beneficially, whereas here maybe it’s not going to be used at all.”

--Lloyd Lee Davis |

"It’s not that I’m opposed to people making money by moving water. I just want to protect our resources...to keep them flowing and provide water for our community first."

--Peggy Postell |

The reason why comes down to simple economics: Kinney County has a population of about 3,500; in 2013, the groundwater district had an annual budget of $200,000. With that, the district is meant to permit the judicious use of water, for uses within the county and without. A full twelve years after the Kinney County GCD was formed, its first network of 6 monitoring wells was installed. Before then, like many groundwater districts, it had relied on volunteers to install and inspect its monitoring wells over its 1,365 square mile territory—an area roughly the same size as the state of Rhode Island. The situation in Kinney County is improving, slowly; today, the district has 13 monitoring wells whose hourly measurements are collected twice a year.

The trouble is, science and observation can only occupy so much of the budget of a groundwater district--lawyer’s fees inevitably claim the rest.

Davis was one of the community leaders who championed the idea of Kinney County creating a one-county groundwater district on the heels of a successful Legislative bid to keep out of the adjacent Edwards Aquifer Authority. In retrospect, the autonomy the county won came with a heavy cost.

For while the district’s formation received overwhelming voter support, the subsequent parceling of water and the slew of hopeful water deals it precipitated created a Hatfield and McCoy dynamic that still persists nearly a decade after the water export furor hit its peak.

The discord can be summed up as a debate on whether the county had excess water to market outside its borders. As with many districts, the county issued permits based on claims of historic use, giving existing water users the right to withdraw up to the maximum ever used on their land. So if you used 7,000 acre-feet in 1963, you were entitled to use up to 7,000 acre-feet a year. If your neighbor used 10,000 acre-feet in 1975, he got 10,000 acre-feet a year. All in all, when the permits were doled out, the total water allocated in the county came to nearly 75,000 acre-feet/year, far more than the amount of water that was ever produced in Kinney County in a single year.

The water used in Kinney County today is nowhere close to reaching permitted capacity. Between 2004 and 2007, groundwater users collectively pumped no more than 4,629 acre-feet a year. From the perspective of some landowners, that added up to a whole lot of excess water that should be made available for sale.

The applications for water export began to flood in shortly after the Groundwater District was formed. Before long, so did the lawsuits. Some landowners alleged that the District was unnecessarily limiting their piece of the pie, while others complained that their neighbors were being given too much water. Litigation over groundwater permits can take years to resolve, grinding its way through the courts until a hearing is denied or someone runs out of money. Sometimes the latter is the objective; the board minutes of June 9, 2009 contain an invigorating account of one marketer’s threats to “bankrupt Kinney County and bury the Board.”

So far, none of the proposed water transport deals in Kinney County have been permitted—for one reason, the District’s rules prohibit issuance of a transport permit without a proven buyer, and no city has actually signed a contract.

For Lloyd Lee Davis, the years of mudslinging have led him to question the wisdom of local control. “I do think water should be managed to the benefit of all people. Others believe it should only be managed for the good of those in Kinney County. I think we are all part of an entity called the State of Texas. And in areas like this, with excess water available to us, maybe that water could be used elsewhere more beneficially, whereas here maybe it’s not going to be used at all.”

Davis’ fellow board member, Peggy Postell, dates her family roots in Kinney County to the 1850s. Her cousin lives on the ranch just north of her, her sister on the ranch above that, all three of them straddling Pinto Creek, a string of flowing artesian wells that make this pretty much the only economically productive crop land in the county. Postell’s wells had run dry in 2010, before the worst of the drought hit, and she spent several years hauling water in gallon containers and showering at her sister’s.

Even as the water in her wells and Pinto Creek dropped, neighbors upstream and downstream continued to market their water. In a normal year of rainfall, she is not opposed to landowners marketing their water: “It’s not easy to make a living in Kinney County. It’s not easy to make a living in agriculture anywhere. So it’s not that I’m opposed to people making money by moving water. I just want to protect our resources so we can still enjoy Pinto Creek, Las Moras Springs, the Nueces River, to keep them flowing and provide water for our community first. ”

What concerns Postell is the lack of precedent for Groundwater Conservation Districts successfully limiting water exports once they have been permitted. Once investors sink tens of millions of dollars into a water pipeline, can they afford to pump less during the bad years? And with an annual budget of $200,000, can the Groundwater Conservation District afford to fight them in court?

The trouble is, science and observation can only occupy so much of the budget of a groundwater district--lawyer’s fees inevitably claim the rest.

Davis was one of the community leaders who championed the idea of Kinney County creating a one-county groundwater district on the heels of a successful Legislative bid to keep out of the adjacent Edwards Aquifer Authority. In retrospect, the autonomy the county won came with a heavy cost.

For while the district’s formation received overwhelming voter support, the subsequent parceling of water and the slew of hopeful water deals it precipitated created a Hatfield and McCoy dynamic that still persists nearly a decade after the water export furor hit its peak.

The discord can be summed up as a debate on whether the county had excess water to market outside its borders. As with many districts, the county issued permits based on claims of historic use, giving existing water users the right to withdraw up to the maximum ever used on their land. So if you used 7,000 acre-feet in 1963, you were entitled to use up to 7,000 acre-feet a year. If your neighbor used 10,000 acre-feet in 1975, he got 10,000 acre-feet a year. All in all, when the permits were doled out, the total water allocated in the county came to nearly 75,000 acre-feet/year, far more than the amount of water that was ever produced in Kinney County in a single year.

The water used in Kinney County today is nowhere close to reaching permitted capacity. Between 2004 and 2007, groundwater users collectively pumped no more than 4,629 acre-feet a year. From the perspective of some landowners, that added up to a whole lot of excess water that should be made available for sale.

The applications for water export began to flood in shortly after the Groundwater District was formed. Before long, so did the lawsuits. Some landowners alleged that the District was unnecessarily limiting their piece of the pie, while others complained that their neighbors were being given too much water. Litigation over groundwater permits can take years to resolve, grinding its way through the courts until a hearing is denied or someone runs out of money. Sometimes the latter is the objective; the board minutes of June 9, 2009 contain an invigorating account of one marketer’s threats to “bankrupt Kinney County and bury the Board.”

So far, none of the proposed water transport deals in Kinney County have been permitted—for one reason, the District’s rules prohibit issuance of a transport permit without a proven buyer, and no city has actually signed a contract.

For Lloyd Lee Davis, the years of mudslinging have led him to question the wisdom of local control. “I do think water should be managed to the benefit of all people. Others believe it should only be managed for the good of those in Kinney County. I think we are all part of an entity called the State of Texas. And in areas like this, with excess water available to us, maybe that water could be used elsewhere more beneficially, whereas here maybe it’s not going to be used at all.”

Davis’ fellow board member, Peggy Postell, dates her family roots in Kinney County to the 1850s. Her cousin lives on the ranch just north of her, her sister on the ranch above that, all three of them straddling Pinto Creek, a string of flowing artesian wells that make this pretty much the only economically productive crop land in the county. Postell’s wells had run dry in 2010, before the worst of the drought hit, and she spent several years hauling water in gallon containers and showering at her sister’s.

Even as the water in her wells and Pinto Creek dropped, neighbors upstream and downstream continued to market their water. In a normal year of rainfall, she is not opposed to landowners marketing their water: “It’s not easy to make a living in Kinney County. It’s not easy to make a living in agriculture anywhere. So it’s not that I’m opposed to people making money by moving water. I just want to protect our resources so we can still enjoy Pinto Creek, Las Moras Springs, the Nueces River, to keep them flowing and provide water for our community first. ”

What concerns Postell is the lack of precedent for Groundwater Conservation Districts successfully limiting water exports once they have been permitted. Once investors sink tens of millions of dollars into a water pipeline, can they afford to pump less during the bad years? And with an annual budget of $200,000, can the Groundwater Conservation District afford to fight them in court?

|

The experience of Kinney County has caused consternation in neighboring Val Verde County.

Although it receives little more than 20 inches of rain a year, Val Verde has the good fortune of being above an especially prolific portion of the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer. 250 million years ago, this desert was an inland sea. As the Permian Sea retreated, it abandoned billions of microsopic invertebrates, which, compacted and fossilized by tectonics and time, formed the limestone rock under present-day Val Verde County. Millions of years of rainfall have etched its course through this subterranean landscape. These conduits, which can be thought of like pipes in a sponge, are natural aqueducts that pipe the rainfall of the western Edwards Plateau—an area roughly the size of Connecticut—to Val Verde County. The result is a desert region of prolific water: on average, this one county contributes one-third of the flow that passes through the Lower Rio Grande Valley. In the past few years, interest in Val Verde’s groundwater has been multiplying among cities and oil and gas producers. The outsiders eyeing Val Verde’s water are in search of a near-mythic supply, one that is reliable in wet and dry years, and especially in years of prolonged drought. It is not only the abundance of water in Val Verde that has caught their eye, but the absence of groundwater regulation. Val Verde is one of the state’s so-called “white areas” where the Rule of Capture still applies, unfettered by pumping limits. Sandra Fuentes works for the Border Organization, a community group that has organized around groundwater protection in Val Verde County. According to Fuentes, the citizens of Val Verde are paralyzed by conflicting information on groundwater districts—do they allow counties to restrict water use for future supply security, or enable water export projects by creating a streamlined permitting process? According to Fuentes, people in Val Verde fear repeating the experience of their neighbor: "Kinney County GCD has been sued up to their eyeballs. It was brother against brother in that community.” Neither aspiring water exporters nor conservation advocates could figure out whether having a district would help or hinder their interests, which goes to show you just how fraught the state of groundwater regulation is in Texas.

|

In the summer of 2014, Jerry Simpton, President of the Del Rio Bank & Trust, confirmed that he, along with others in Val Verde’s leadership, believed it was better to go without a groundwater conservation district until a water marketing deal with legs forced its creation. “For a time, I was among those who believed we needed a district to protect local control of our water,” Simpton says. “But I’ve been looking at the court cases coming down in Texas and legislation [being passed], and have realized that the water laws of Texas are so convoluted that it's nearly impossible to figure out how to manage it. Tell me how to do it so we don't spend all the district’s money on legal fees and so we can actually manage the water.”

Since 2005, various attempts to create a Groundwater Conservation District in Val Verde have been abandoned. The latest effort in the 2015 Legislature never passed out of committee, the victim of sustained indecision on both sides. Neither aspiring water exporters nor conservation advocates could figure out whether having a district would help or hinder their interests, which goes to show you just how fraught the state of groundwater regulation is in Texas.

Since 2005, various attempts to create a Groundwater Conservation District in Val Verde have been abandoned. The latest effort in the 2015 Legislature never passed out of committee, the victim of sustained indecision on both sides. Neither aspiring water exporters nor conservation advocates could figure out whether having a district would help or hinder their interests, which goes to show you just how fraught the state of groundwater regulation is in Texas.

|

|

TOO BIG TO FAIL |

|

The question of whether to regulate groundwater is not resolved by the formation of a groundwater district.

Four hundred miles north of Val Verde County, groundwater has been regulated for as long as state law has permitted it. There, the farmers have chosen to pump their lands dry, and even efforts to cut pumping to meet planned depletion have been met with resistance.

Four hundred miles north of Val Verde County, groundwater has been regulated for as long as state law has permitted it. There, the farmers have chosen to pump their lands dry, and even efforts to cut pumping to meet planned depletion have been met with resistance.

|

In much of the state, as in the Ogallala, the rules we set for how much groundwater can be pumped each year have little to do with how much water the land can sustainably provide, but instead how much we are intent on taking from it.

The Llano Estacado extends southward from just south of Amarillo to about 100 miles south of Lubbock. The region used to be the headwaters of the Brazos and the Colorado Rivers, back when the Ogallala Aquifer saturated the sandy soils of the plains all the way to the surface. No one alive today remembers that time; for as long back as living memory extends, the Ogallala has been on a steady decline as it services the irrigation pivots of 4.4 million acres of cotton, corn and wheat. (source) Over the last half century, the groundwater table of the Ogallala has gradually been drained off; in Parmer County, on the state’s western edge, total storage fell by half between 1958 and 2008.

|

|

"We're not talking about conserving water, we're talking about controlling water."

--Written On Water, Official Trailer

--Written On Water, Official Trailer

The 1968 State Water Plan recognized this looming groundwater deficit, imagining a grand aqueduct from the Mississippi River, arcing north of Dallas-Fort Worth to deliver irrigation waters to the Llano Estacado. It was a Space Age vision of technological triumph on par with California’s State Water Project, which broke ground just 8 years before. Unlike California’s grand aqueduct, which delivers millions of acre-feet of Northern California snowmelt each year to Southern California, Texas’ Mississippi aqueduct never saw realization.

Sixty years later, no new irrigation supplies are coming to the farmers of the Llano Estacado. 2.4 million acre-feet less water will run through irrigation pivots in 2060 than in 2012, because that water will no longer be available for use—it will already have been drawn down for 50 years of corn and cotton. If the region meets its Desired Future Conditions, the Ogallala will have been depleted by another 50% from present conditions in 50 years. If water use in the state’s southern high plains follows its historic course, there will be little meaningful water in the Ogallala by 2100. By then, farmers will have reverted to the dry land farming techniques of their great-grandfathers. Or more likely, they will have stopped farming altogether, and either the state’s cotton bowl will have reinvented itself or it will have blown away like topsoil.

Sixty years later, no new irrigation supplies are coming to the farmers of the Llano Estacado. 2.4 million acre-feet less water will run through irrigation pivots in 2060 than in 2012, because that water will no longer be available for use—it will already have been drawn down for 50 years of corn and cotton. If the region meets its Desired Future Conditions, the Ogallala will have been depleted by another 50% from present conditions in 50 years. If water use in the state’s southern high plains follows its historic course, there will be little meaningful water in the Ogallala by 2100. By then, farmers will have reverted to the dry land farming techniques of their great-grandfathers. Or more likely, they will have stopped farming altogether, and either the state’s cotton bowl will have reinvented itself or it will have blown away like topsoil.

The Panhandle was the first part of the state to form groundwater districts, but the choices locals made as to how to manage groundwater highlight the difference between regulating groundwater and sustaining groundwater. For the vast majority of the Ogallala in the Texas Panhandle is managed under the 50/50 rule, leaving only 50% of the water that is available in the aquifer today in 50 years. Even the attempts to actually limit pumping so that target could be met inspired a revolt in the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District. Plans to require water meters on farms that pump millions of gallons a day have been suspended, and the leadership who dared to enforce the rules, sacked.

The tensions between farmers who want to sustain their groundwater for the next generation and those who successfully resisted regulation is beautifully detailed in the upcoming film Written on Water. "What are we really talking about here?" asks a farmer in the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District. "We're not talking about conserving water, we're talking about controlling water."

The planned depletion of the Ogallala is a cautionary tale often cited by opponents of groundwater projects across the state as evidence of the profligacy of past and present generations, and the risks to the future viability of regions whose water resources seem too productive to fail.

The tensions between farmers who want to sustain their groundwater for the next generation and those who successfully resisted regulation is beautifully detailed in the upcoming film Written on Water. "What are we really talking about here?" asks a farmer in the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District. "We're not talking about conserving water, we're talking about controlling water."

The planned depletion of the Ogallala is a cautionary tale often cited by opponents of groundwater projects across the state as evidence of the profligacy of past and present generations, and the risks to the future viability of regions whose water resources seem too productive to fail.

|

In much of the state, as in the Ogallala, the rules we set for how much groundwater can be pumped each year have little to do with how much water the land can sustainably provide, but instead how much we are intent on taking from it.

But the Ogallala tells us less about the future of water in the state than it may seem on the surface. Conditions in the Ogallala that virtually ensure its failure separate it from many of Texas’ other major aquifers. In the Ogallala, the water stays cheap—the only infrastructure needed is the pump to draw it out of the ground and the irrigation pivot to deliver it to crops. There are no local substitutes with which to diversify, since the Panhandle receives only marginal river inflows. There is virtually no economic diversity either: the entire local economy hinges on agriculture. Once locals saw the writing on the wall, the only choice to be made was to keep mining the ground for water or to switch to dry land farming and see your own production plummet as your neighbors continue to pump the water beneath your land. |

|

The demographics driving demand upward in most of the state’s other major aquifers are fundamentally different, the function of urban migration and expansion whose ability to pay for water infrastructure eclipses the farmers in the High Plains, and who have a far greater diversity of water resources within regional range. Unlike agriculture in the Panhandle, the urban growth driving the state’s growing demands does not necessarily spell the destruction of the state’s water–not if that growth can adapt to use water differently, and not if our infrastructure and water management can adapt along with it.

|

|

BALANCING THE BUDGET |

|

Consider a water importer who takes as much water as the locals, a farmer in the Panhandle who resists pumping restrictions, and the owner of a new ranchette whose 10 acres are exempt from groundwater limits--is one more virtuous or vile than the others? The end result is the same: less water for future generations who were never afforded the choice of what would be left for them.

Groundwater has never been more precious than it will be to future residents of Texas, the 40 million of them who will see deeper droughts and drier rivers than the people who first tapped the ground. Managed for sustainable yield--taking only as much out as nature puts back in--groundwater is reliable and cheap. There is no source that can replace it, no technology that will magically make seawater as cheap to desalt and pump. No reservoirs in the world have ever been constructed that rival the storage capacity of our aquifers. They are some of nature's greatest infrastructure.

It is impossible to imagine how Texans can weather the coming century if we don't direct development toward the water resources least likely to fail and limit our demands on those that are already failing. While the state has shown itself willing to facilitate development of new groundwater resources, and to subvert local control to do so, it has not yet demonstrated its willingness to breach that inviolable boundary to prevent us from pumping ourselves dry.

All around us, our Western neighbors have undertaken bold reforms to ensure that groundwater resources can be sustained. In parts of Arizona and Oklahoma's Arbuckle-Simpson Aquifer, the state has limited groundwater production to maintain ground and surface water supplies. In Montana and Nevada, groundwater production is only permitted if it can be shown that doing so will not take surface or groundwater from anyone else. Even California--which, to the satisfaction of many Texans, has been even more stubbornly resistant to reasonable water reforms than any other Western state--in 2014 finally acted to manage its precipitously declining groundwater resources, requiring all priority basins to be sustainably managed by 2040.

We can look within Texas, too, to find places where people have acted to limit their demands on the water that the ground can provide.

San Antonio and its neighbors have turned to the Carrizo Aquifer because they have had to ease back from pumping in the Edwards Aquifer, where for the most part, production is limited to sustainable yield. The efforts in the Edwards were far from homegrown. The farmers and cities over the aquifer share their water with species protected under the Endangered Species Act, and they learned to cooperate under the duress of federal intervention: either they would figure out how to use less water, or the government would do it for them.

In parts of the Gulf Coast Aquifer, people have stomached draconian limits on groundwater production because the damage from their pumping was so inescapably obvious and fast-moving: entire neighborhoods had been swallowed by the Galveston Bay as the land, deprived of its cushion of underground water, sank beneath them. Today the memorial obelisk of the San Jacinto battlefield rises from a marshland of man's making, doubly commemorating those who died for Texas independence and the ravages of unfettered pumping.

Can Texans make the choice to protect their own water where no federal authority or encroaching seas are forcing their hand? And if locals aren't willing to do it, which should the state find more distasteful: letting them dry up and blow away, or compelling us all to restrain our use so that Texans will always have enough water to thrive?

The answers to those questions will determine whether the Texas Miracle has a hope of outlasting cotton on the High Plains.

Groundwater has never been more precious than it will be to future residents of Texas, the 40 million of them who will see deeper droughts and drier rivers than the people who first tapped the ground. Managed for sustainable yield--taking only as much out as nature puts back in--groundwater is reliable and cheap. There is no source that can replace it, no technology that will magically make seawater as cheap to desalt and pump. No reservoirs in the world have ever been constructed that rival the storage capacity of our aquifers. They are some of nature's greatest infrastructure.

It is impossible to imagine how Texans can weather the coming century if we don't direct development toward the water resources least likely to fail and limit our demands on those that are already failing. While the state has shown itself willing to facilitate development of new groundwater resources, and to subvert local control to do so, it has not yet demonstrated its willingness to breach that inviolable boundary to prevent us from pumping ourselves dry.

All around us, our Western neighbors have undertaken bold reforms to ensure that groundwater resources can be sustained. In parts of Arizona and Oklahoma's Arbuckle-Simpson Aquifer, the state has limited groundwater production to maintain ground and surface water supplies. In Montana and Nevada, groundwater production is only permitted if it can be shown that doing so will not take surface or groundwater from anyone else. Even California--which, to the satisfaction of many Texans, has been even more stubbornly resistant to reasonable water reforms than any other Western state--in 2014 finally acted to manage its precipitously declining groundwater resources, requiring all priority basins to be sustainably managed by 2040.

We can look within Texas, too, to find places where people have acted to limit their demands on the water that the ground can provide.

San Antonio and its neighbors have turned to the Carrizo Aquifer because they have had to ease back from pumping in the Edwards Aquifer, where for the most part, production is limited to sustainable yield. The efforts in the Edwards were far from homegrown. The farmers and cities over the aquifer share their water with species protected under the Endangered Species Act, and they learned to cooperate under the duress of federal intervention: either they would figure out how to use less water, or the government would do it for them.

In parts of the Gulf Coast Aquifer, people have stomached draconian limits on groundwater production because the damage from their pumping was so inescapably obvious and fast-moving: entire neighborhoods had been swallowed by the Galveston Bay as the land, deprived of its cushion of underground water, sank beneath them. Today the memorial obelisk of the San Jacinto battlefield rises from a marshland of man's making, doubly commemorating those who died for Texas independence and the ravages of unfettered pumping.

Can Texans make the choice to protect their own water where no federal authority or encroaching seas are forcing their hand? And if locals aren't willing to do it, which should the state find more distasteful: letting them dry up and blow away, or compelling us all to restrain our use so that Texans will always have enough water to thrive?

The answers to those questions will determine whether the Texas Miracle has a hope of outlasting cotton on the High Plains.