|

|

THE CONNECTING THREAD |

|

The menu at the RecordBuck Ranch in Utopia, Texas caters to a wide variety of tastes. Novice hunters can try their hand at a javelina for $500. Trophy racks of exotic antelope will cost the discerning hunter quite a bit more. And for the hunter who’s had it all, there’s the white buffalo, at $30,000 a kill.

The RecordBuck is home to another rarity, this one unadvertised: the Seco Sinkhole. The Seco is a monstrous portal into the earth some 40 feet across and 75 feet deep. When the rains come to these brushy hills, its rock walls transform into a vortex, funneling water into the caverns of the Edwards Aquifer below. In a typical year, the water that falls through this one hole in the ground will supply roughly 80,000 homes in San Antonio with their drinking water. (source)

On a spring day in 2013, I stood on a rock ledge at the Seco’s lip, experiencing that dread unique to subway platforms and canyon walls: what if for an instant some perverse impulse overtook me, and I were to fling myself over the edge? One of my companions—a hunting guide who was glad not to be spending a slow afternoon in his trailer—stood easily on a neighboring ledge. He had walked the Seco when it was flowing fast, when a clumsy step or a loose rock could mean a descent into the maelstrom and being forever laid to rest in the depths of the Edwards Aquifer.

The RecordBuck is home to another rarity, this one unadvertised: the Seco Sinkhole. The Seco is a monstrous portal into the earth some 40 feet across and 75 feet deep. When the rains come to these brushy hills, its rock walls transform into a vortex, funneling water into the caverns of the Edwards Aquifer below. In a typical year, the water that falls through this one hole in the ground will supply roughly 80,000 homes in San Antonio with their drinking water. (source)

On a spring day in 2013, I stood on a rock ledge at the Seco’s lip, experiencing that dread unique to subway platforms and canyon walls: what if for an instant some perverse impulse overtook me, and I were to fling myself over the edge? One of my companions—a hunting guide who was glad not to be spending a slow afternoon in his trailer—stood easily on a neighboring ledge. He had walked the Seco when it was flowing fast, when a clumsy step or a loose rock could mean a descent into the maelstrom and being forever laid to rest in the depths of the Edwards Aquifer.

|

I had come to the Seco to see where it was that water entered underground, something that at the time I mistook as being a phenomenon as uncommon as the sinkhole itself.

What I learned in two years of exploring water in Texas is that the Seco is just a dramatic and violent example of something commonplace in Texas: rainfall disappears underground on private land, where it becomes a critical resource for millions of people, most of whom live hundreds of miles from where that water first landed on Texas soil. |

|

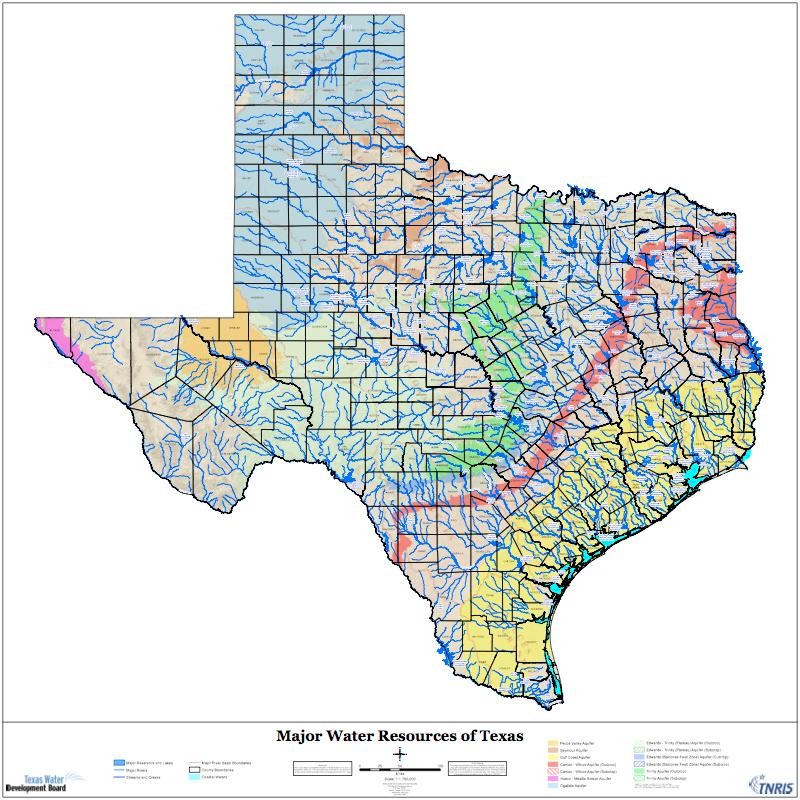

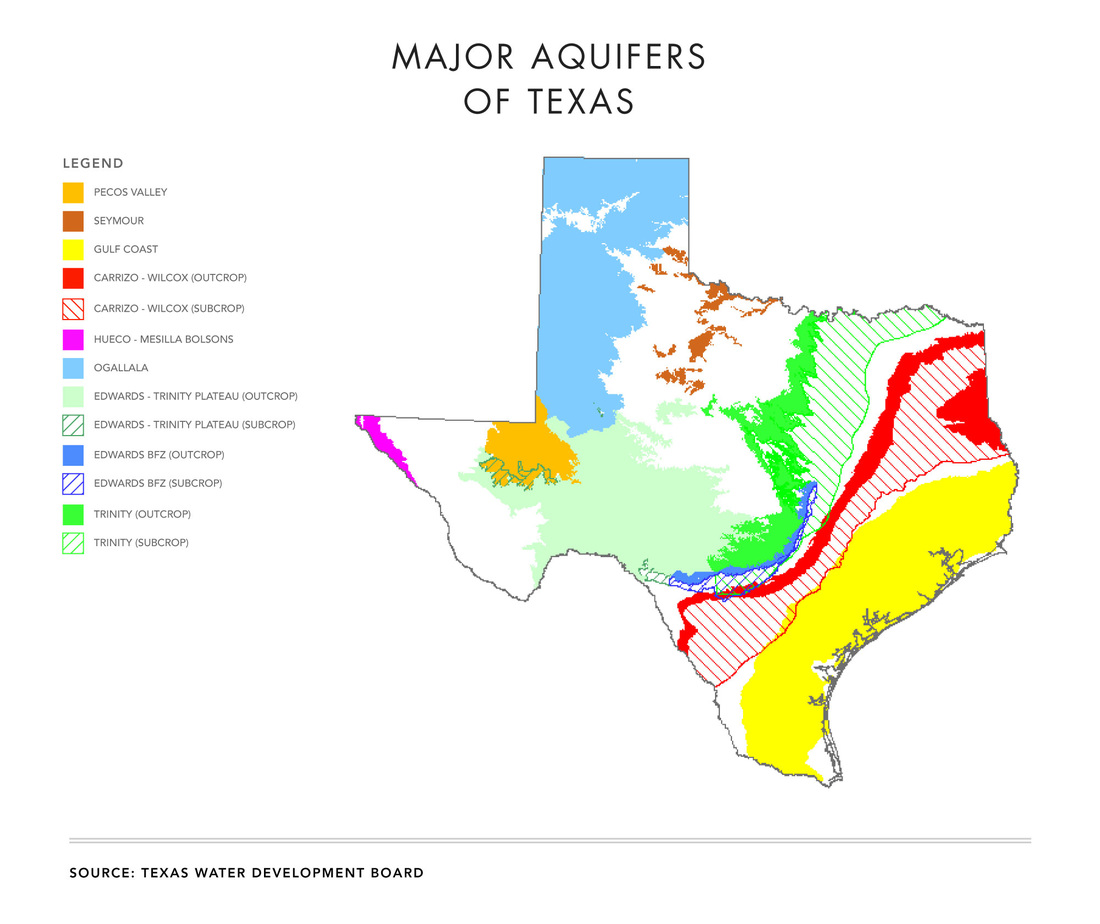

The behavior of water on and beneath private land is the key to preserving water for Texans in the 21st century and into the 22nd, a grand challenge that is uniquely Texan. Other western states have urban populations far removed from their water sources, but that’s where the similarities end. In California, Colorado, New Mexico and their western neighbors, water starts as snow in mountain ranges on federal lands, and is piped to distant cities through massive infrastructure managed by federal or state governments. Not so in Texas, where more than 95% of land is privately owned. Here, most of the storage and distribution of water happens on private land—not in manmade pipes or reservoirs, but beneath the earth, in the ancient rock and sand that lie beneath the houses and farms and ranchlands of Texas.

|

The aquifers of Texas store 500 times more water than all of our rivers and lakes combined.

|

|

The water that we see above ground here in Texas is a mere 0.2 percent of the water in the state. The aquifers of Texas—the rocks and sand deposited by millions of years of glacial formation and melt water, volcanic eruptions, the advance and retreat of ancient seas, that geologic history that underlies the world as we experience it on the surface—store 500 times more water than all of our rivers and lakes combined.

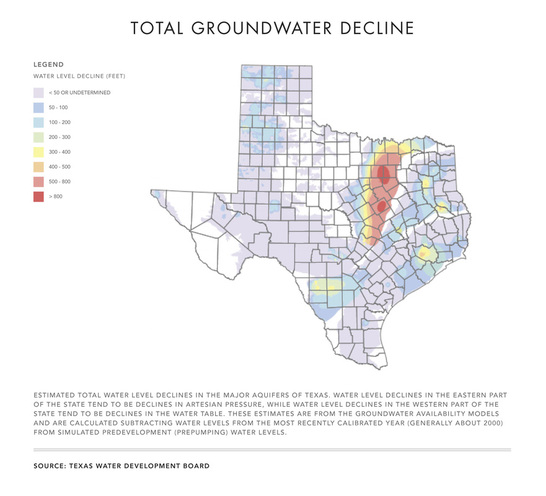

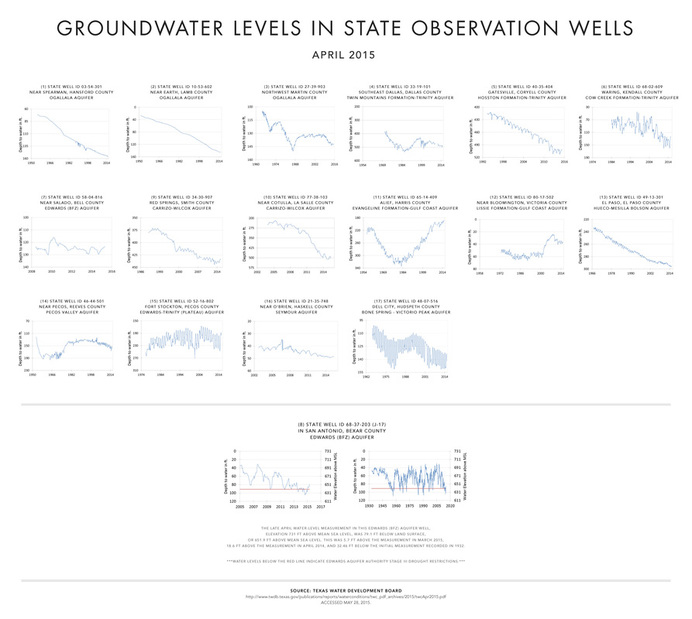

Ever since this land was settled, Texans have relied on this underground water to get them through dry spells. As a half-decade drought shriveled our water supplies on the surface, and the new subdivisions and fracking sites demanded more water, Texans have come to rely ever more on these hidden caches of water. In 2012, the Texas Water Development Board estimated that 60% of the water used in the state came from groundwater aquifers. Alongside open carry legislation and other bills that garnered media attention, the 2015 Legislature quietly passed several bills designed to further amplify groundwater production.

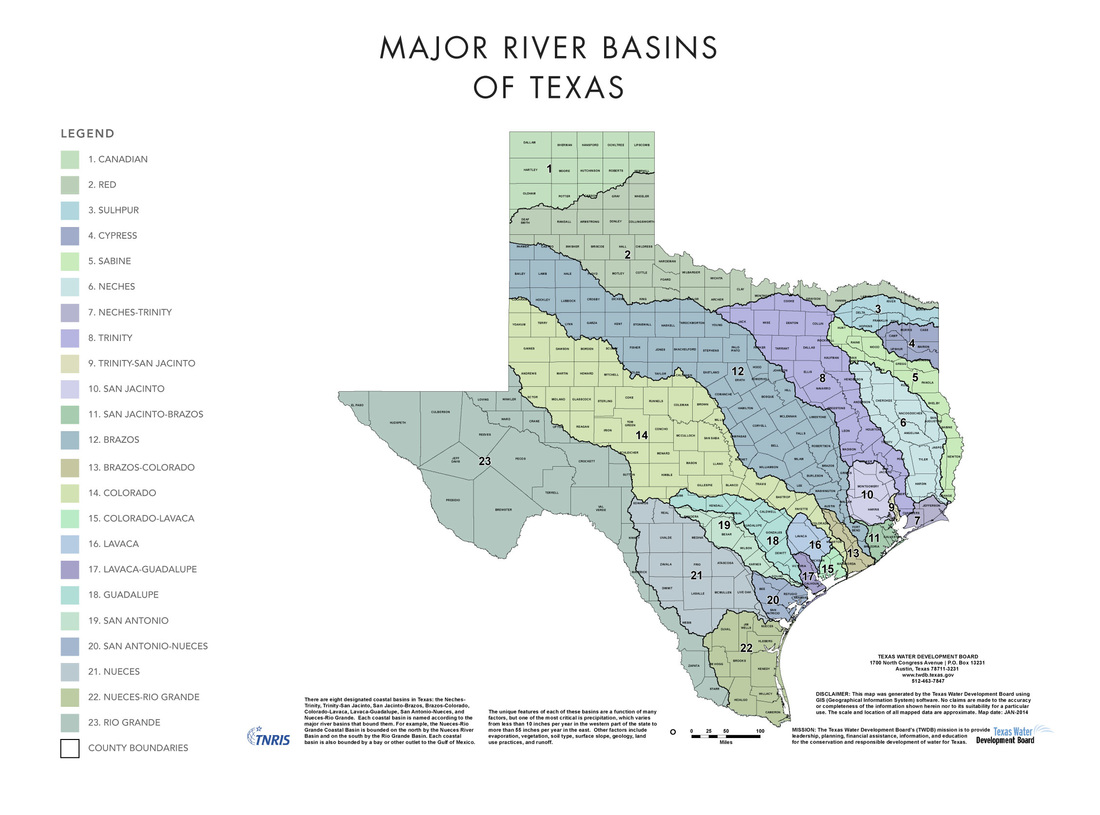

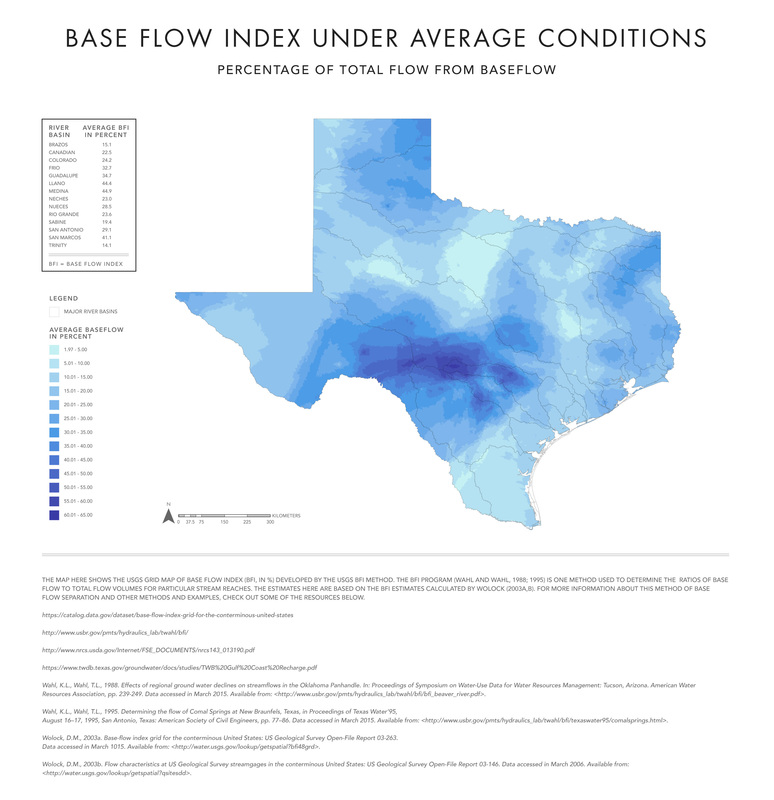

So in an era of epic drought and unending growth, the question is: how much should we pump, and how fast? The answer to this question will affect the 40 million Texans who will one day call this place home. And not just because it will determine how much water we take out of the ground, but also how much water is left of the water above ground. In times of drought, as much as 80% of the water in some of Texas' rivers can come from water below ground.

|

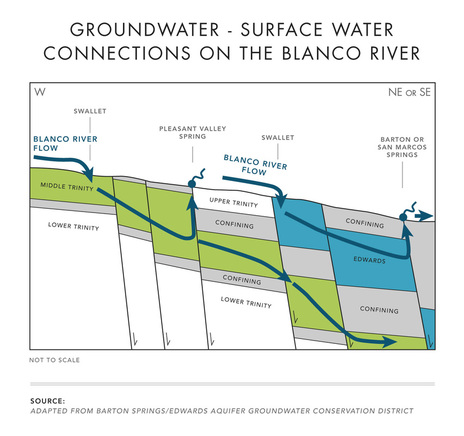

That’s because in Texas, rivers are born from the water below ground. There is no river in Texas that gets less than 15 percent of its flow from the water seeping in from below. For rivers in Central Texas, that number swells to 40 percent. In times of drought, this dependence amplifies, and as much as 80% of the water in some of Texas' rivers can come from water below ground. In places like the Seco Sinkhole, this happens quickly, a spring rainstorm pumping millions of gallons of water into the Edwards Aquifer. In other places, the water that today is flowing through a river may have spent hundreds or even thousands of years below ground before finally making its way to the surface.

As I stood at the Edward’s mouth that day on the edge of the Seco, I realized that to understand the connection between the water above and below the ground, I would have to go further than just staring into a hole in the ground. I would need to look into an aquifer. Fortunately, I knew who to ask.

As I stood at the Edward’s mouth that day on the edge of the Seco, I realized that to understand the connection between the water above and below the ground, I would have to go further than just staring into a hole in the ground. I would need to look into an aquifer. Fortunately, I knew who to ask.

|

|

EYES INTO THE TRINITY |

|

Earlier the same spring, I’d met Gregg Tatum while swimming at Jacob’s Well, a smaller-scale version of what Seco Sinkhole used to be—an opening in the earth where the water below ground rises to the surface. The Spanish called these ojos: eyes into the earth. Jacob’s Well, a nearly perfect cylinder cut into the limestone face of the Hill Country, is an eye into the Trinity Aquifer.

On that day, Tatum’s arrival had been announced by a stream of tiny bubbles rising from the depths of the well. A few minutes later, Tatum rose to the surface, an amphibious creature in black neoprene.

On that day, Tatum’s arrival had been announced by a stream of tiny bubbles rising from the depths of the well. A few minutes later, Tatum rose to the surface, an amphibious creature in black neoprene.

|

|

Tatum heads the Jacob’s Well Exploration Project, a band of cave divers who can claim the rare distinction of swimming through aquifers. On any given Sunday, Tatum and his dive partner, David Moore, are suiting up to force themselves through subterranean currents wherever the earth offers a space large enough for a human body to pass.

When it comes to cave divers, you realize that “large enough” is a state of mind. To move from Jacob’s Well into the tunnels that feed it water, Tatum and Moore have to squeeze through a restriction in the rock only 14” across. They do this while 55’ underwater, with two tanks of air strapped to their bodies, hauling Diver Propulsion Vehicles, personal engines that pull them through the water. |

“The problem that we encounter is that this slope is made of gravel. The gravel is right at the angle of repose and it tends to want to cascade downward with any small disturbance,” Tatum shares in his nonchalant way. “At certain times the gravel will almost completely seal the restriction so our technique is to literally swim through the gravel. We’ll inch forward, we’ll push more gravel, we’ll inch forward, we’ll push more gravel aside, we’ll inch forward, until we’re fully inside the next portion of the cave. We have seen instances in which the gravel will completely fill in behind us, so it’s a little unsettling but you learn to cope with it.”

|

Eleven people have died while diving Jacob’s Well, not all of them novices. As a result, recreational diving is strictly prohibited. The Jacob’s Well Exploration Project is permitted to dive in the name of science. When the team isn’t repairing guidelines or caching air tanks for future divers, they are collecting data on the Trinity Aquifer, Hays County’s primary water source. The team has charted over 6,000 feet of tunnels leading from the well opening, and have donated their survey maps and data to Hays County, universities, community advocates, and the Hays-Trinity Groundwater Conservation District.

The question of where the water in Jacob's Well comes from was once just a curiosity. Now the ability to answer that question determines whether there any water will remain in Jacob's Well. |

Groundwater pumping in Hays County has quadrupled since the nineties, as the county has grown at breakneck pace. The effects can be seen at Jacob’s Well, though it may only be old timers who notice the difference. In the middle part of last century, when not much existed in Hays County beyond goat ranches and summer camps, the water streaming out of Jacob’s Well flowed so fast and strong, swimmers would be pushed aside by its force.

|

“There’s a municipal public water system just adjacent here and you can actually see when they energize their wells.” - Gregg Tatum

|

It has been more than a decade since there has been a steady current in Jacob's Well. The new housing subdivisions that have sprung up in the area draw their water from wells in the Trinity Aquifer. With each new well there is less water in the tunnels feeding Jacob's. It is such a responsive system, you can see the effect of groundwater pumping in real time in the flow instrument readings outfitted at the base of Jacob’s Well. Says Tatum, “there’s a municipal public water system just adjacent here and you can actually see when they energize their wells” by the drop in flow at Jacob’s. As subdivisions continued to pump during the recent drought, the flow at Jacob's Well slowed, and in 2010, completely stopped. It was the first time in recorded history that the well ceased its flow.

|

|

Less flow in Jacob's Well means less flow in the Blanco, which also means less flow in the springs of the Edwards Aquifer.

|

The clear connection between groundwater pumping and flow in Jacob's Well hasn't stemmed demand for more groundwater permits. One such permitted project is “a golf course which [is] directly over the aquifer," says Tatum. Using data collected by the Exploration Project, local advocates have pushed back on the golf course water permit, arguing, as Tatum puts it is "not a wise use of the resource. If every project that has been proposed is built, zero flow conditions in Jacob’s Well may one day be the norm.

On the surface, it would seem that what happens to Jacob’s Well is a matter of concern only to the locals. But the value of Jacob's Well ripples far beyond the town of Wimberley and its cypress-lined swimming holes. Just beyond this weekend Mecca's rope swings and antique shops, the creek formed by Jacob's Well merges into the Blanco River, which cuts southward near San Marcos and keeps flowing all the way to the Gulf, somewhere near Victoria. Less flow in Jacob's Well means less flow in the Blanco, which--in a strange twist that captures the complexities of Texas hydrology--also means less flow in the springs of the Edwards Aquifer. Researchers were surprised to discover a few years ago that some of the water in the Blanco River downstream of Jacob’s Well did something greatly unexpected: it went underground. Not all of it - Some of it kept flowing aboveground just as we would expect a river would - but quite a bit of it was disappearing down a formation called the Johnson Swallet and entering into the Edwards Aquifer. At that point, it did something even more surprising: some of that water flowed north about 40 miles, emerging a few months later in Austin’s Barton Springs, which flows into the Colorado River. And some of it took a southward course and was detected later 40 miles southeast at San Marcos Springs, merging eventually with the Blanco River. This is the story of water in Texas: water aboveground escapes below, and water below ground springs up above, making for a much more complicated world than any map would lead you to believe. Understanding that subterranean landscape, and what it means for our world above ground, is what brings the members of the Jacob’s Well Exploration Project back, says David Moore: "what's surprising to us is, we normally come into it with the idea of exploration but we come out with the idea of helping everyday people and what does water mean to everyone else." |

Last summer on a dive trip to West Texas, Moore suffered a rattlesnake bite to the leg. Surgeons in Midland removed part of the muscle in his right leg; he narrowly avoided amputation. For a cave diver—whose ability to execute tightly controlled kicks in extreme conditions can mean the difference between life and death—this is a very serious injury.

|

Yet Moore and Tatum continue to dive together through deadly environments thousands of feet from the surface, a decision based upon the trust they've cultivated over years. Says Tatum: “You don’t go cave diving with just anybody. You have to have a relationship. That sounds really corny, but you’re trusting your life with your partner. David and I have dived together so many times, under such adverse conditions, we have telepathy. But there is no panic, and that’s very reassuring.”

When I asked Tatum if being a cave diver helps him manage the feeling of panic beyond the cave, he chuckled: “The only time I ever experience panic outside of something that might happen underwater is with women.” Aha, I laughed, “Has it helped with that?” “Not at all. Totally different animal.” |

|

|

DESIRED FUTURE CONDITIONS

|

|

In the physical world, water may be weaving its way through the landscape, moving back and forth from the world aboveground to the world below several times in the span of days. But the complexity of the actual world collapses in its translation to our human laws. In the legal world that Texans have constructed, water is either “groundwater” or “surface water,” and the laws that determine how much of each can be used have so little to do with each other, they may as well be oil and water.

|

In Texas, the waters above and below ground are regulated by different entities. The water above ground is owned by the state of Texas, and regulated by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. The water below ground is owned by the landowner and regulated by local groundwater districts--if it is regulated at all (about 20% of the state are so-called "white areas," free of any groundwater regulation).

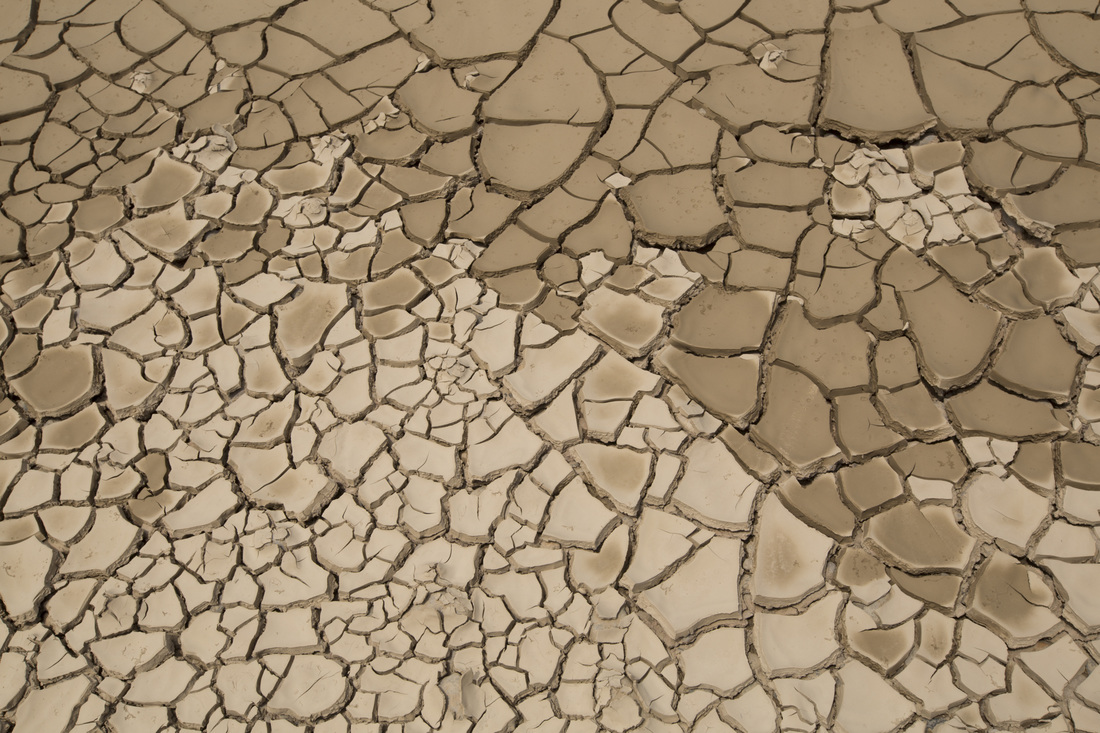

Despite a century of science illuminating the interdependence of surface water and groundwater supplies, the state's water plan does not recognize that a withdrawal from resources below ground may result in less water above ground. In the physical world, as the earth below ground is drained of water, the signs are visible on the surface in the form of dry holes, gravel beds, and grass-choked boulder fields where water once flowed. In the artificial world of state water planning, when we pump water from below the ground, the amount of water above ground stays the same. Yet when you look for the signs of where the hydrological connections between the water below and above ground have been severed, you realize they are everywhere, hiding in plain sight. |

From turn-of-the-century settlement to the farming boom of the postwar years, the water table of Texas was slowly bled off in the name of cotton, winter wheat, spinach and melon. At the turn of the last century, wells tapping the Trinity Aquifer east of Waco would flow to the surface of their own accord, no pump required. By the 1950s, so much water had been allowed to flow freely out of the Trinity, the pressure of the aquifer began to drop. Wells were lowered, and they kept on lowering them as groundwater pumping further depressurized the aquifer. In 1900, a successful well in the northeastern Trinity could be placed barely below the land’s surface. Now in 2015, you will probably have to drill 1,000 feet down to find water. The mineral wells and healing baths of the Trinity Aquifer are now mostly lost to memory, though you can find the grand hotels that once accompanied them.

|

|

|

The Ogallala, among the great American groundwater aquifers—and also likely to be the first to falter under the pressure of irrigated agriculture—was once the headwaters of the Brazos River. The roaring falls and big springs of its many creeks hardly lasted a generation after heavy pumping began; the cotton and corn economy it sustained in the Texas Panhandle is not expected to last for more than another generation.

It is the same story in the southwestern Carrizo. Visit the Winter Garden of South Texas today, and it is nearly impossible to imagine that springs and marshes ever could have lived where mesquite now rules. But not far from Laredo, alligators once patrolled marshlands watered from the springs of the Carrizo Aquifer—until the water demands of spinach, melons and cabbage bled them dry as well.

Silver Falls, Mineral Wells, San Antonio Springs, Carrizo Springs, Big Spring. These are just a few of the names given to waters that no longer flow. How many springs have disappeared, how many creeks have run dry—most of that is lost to human memory. But some people remember.

It is the same story in the southwestern Carrizo. Visit the Winter Garden of South Texas today, and it is nearly impossible to imagine that springs and marshes ever could have lived where mesquite now rules. But not far from Laredo, alligators once patrolled marshlands watered from the springs of the Carrizo Aquifer—until the water demands of spinach, melons and cabbage bled them dry as well.

Silver Falls, Mineral Wells, San Antonio Springs, Carrizo Springs, Big Spring. These are just a few of the names given to waters that no longer flow. How many springs have disappeared, how many creeks have run dry—most of that is lost to human memory. But some people remember.

|

David Langford, for one, remembers the creeks of Hillingdon Ranch.

Since his great-grandfather imported his first cows in 1890, the ranch has produced Angus cattle according to his ethos, which Langford sums up as: “if you have to feed the cows, you have too many cows.” In other words, you should never produce more than the land can sustain. “Those people that come here, they’re living their vision of the American Dream and I don’t want to spoil that for them, but I don’t think they realize where the water comes from." - David Langford

Hillingdon’s Angus cattle are highly prized, every one of them on a lineage charted back to those first cows on the ranch. “The world will beat a path to the door for these animals,” Langford says, “and it all hinged on there being available water.”

|

That water was a sure thing for the first 111 years of the ranch’s operation, assured by the constant flow of the spring-fed creeks fed by the Trinity Aquifer. “The creeks provide all the water for the livestock, and they did all through my teen years,” says Langford. But in 2001, Langford says, the water in his wells began to drop: “From then to 2013, the water level in our well has dropped 60 or so feet.” As the water in the well declined, the perennial springs began to falter. They had dried temporarily in the 1950s drought, but this is the first time in Langford’s life that nearly a full decade has passed without recovery.

“Now that’s very significant because our management practices haven’t changed. We still have a few windmills and a few wells. We have no center pivot, no irrigated agriculture. Our family’s been here six generations, most of the neighbors have been here that long and they all have big ranches as well, so for several miles in all directions there’s essentially no development, no industry, no irrigated ag. So where’s that water going?”

What changed isn’t water use on the ranch, but thousands of groundwater wells that have been drilled in the 50-mile radius around it. This part of the Hill Country is one of the fastest growing parts of the state, and most of that growth has been enabled by groundwater pumping. Newcomers to the area have no idea what the limits of the Trinity Aquifer are, or how the exponential increase in groundwater production has already reshaped the landscape that had otherwise remained unchanged for generations. Langford can see these changes, not only through the eyes of someone who has worked the land for 70 years, but through the eyes of his great-grandfather and the four generations in between who knew the land before the tie between the aquifer and its streams was severed.

“Now that’s very significant because our management practices haven’t changed. We still have a few windmills and a few wells. We have no center pivot, no irrigated agriculture. Our family’s been here six generations, most of the neighbors have been here that long and they all have big ranches as well, so for several miles in all directions there’s essentially no development, no industry, no irrigated ag. So where’s that water going?”

What changed isn’t water use on the ranch, but thousands of groundwater wells that have been drilled in the 50-mile radius around it. This part of the Hill Country is one of the fastest growing parts of the state, and most of that growth has been enabled by groundwater pumping. Newcomers to the area have no idea what the limits of the Trinity Aquifer are, or how the exponential increase in groundwater production has already reshaped the landscape that had otherwise remained unchanged for generations. Langford can see these changes, not only through the eyes of someone who has worked the land for 70 years, but through the eyes of his great-grandfather and the four generations in between who knew the land before the tie between the aquifer and its streams was severed.

Langford had driven us to the top of a hill overlooking the ranch. Cattle ranged under clusters of live oak, and the late afternoon breeze worked the golden grasses below. This was the big sky Texas vision drawing Baby Boomers by the thousands to this part of Central Texas, one of the fastest-growing retirement destinations in the country. Langford could see that vision too, but he could also see the fantasy in it: “Those people that come here, they’re living their vision of the American Dream and I don’t want to spoil that for them, but I don’t think they realize where the water comes from when they turn their tap on or what a green St. Augustine yard means for those of us that are trying to maintain our heritage."

For a six-generation ranching family, this lack of self-determination is an unwelcome visitor. When the fields can no longer support the herd, the herd can be thinned until the land restores itself. Yet no matter how conservative a landowner is with his water, his well will depend on his neighbor's use.

In 1949, the Texas Legislature realized that landowners needed a way to protect their water from being pumped by someone else. So the state permitted the people of Texas to create Groundwater Conservation Districts, which are allowed to limit pumping on private property. Roughly 100 such districts have been created in Texas. The creation of groundwater districts allows local users like Langford to decide how they will collectively manage their groundwater.

For a six-generation ranching family, this lack of self-determination is an unwelcome visitor. When the fields can no longer support the herd, the herd can be thinned until the land restores itself. Yet no matter how conservative a landowner is with his water, his well will depend on his neighbor's use.

In 1949, the Texas Legislature realized that landowners needed a way to protect their water from being pumped by someone else. So the state permitted the people of Texas to create Groundwater Conservation Districts, which are allowed to limit pumping on private property. Roughly 100 such districts have been created in Texas. The creation of groundwater districts allows local users like Langford to decide how they will collectively manage their groundwater.

|

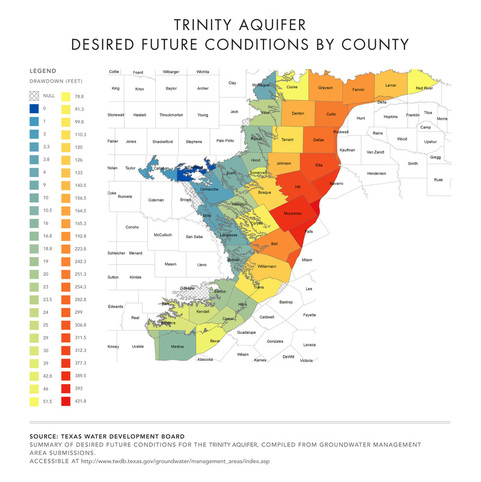

Even with this regulation in place, it turns out that the depletion of aquifers isn't by accident--it's by design.

Every five years, Texas groundwater districts are required to report to the state their targets for how much groundwater will be left in the aquifers they manage in fifty years’ time—targets called “Desired Future Conditions.” Almost without exception, the groundwater districts that have been created to protect landowners from the imprudent actions of their neighbors are managing their aquifers to be drawn down over time. You can think of it like a bank account—in 50 years, do I want to have more, less or the same amount of money? In most places in Texas, the goal is for the planned depletion of the local water account. The reason why is that in most places, the goal of how much water will be left is just the inevitable outcome of how much we want to pump today. |

No matter how conservative a landowner is with his water, his well will depend on his neighbor's use.

|

This is the case for the Trinity Aquifer around the Hillingdon Ranch. As retired Baby Boomers and weekend residents flood into the region, the local water level is planned to drop by another 30 feet over the next 50 years, a policy decision that chagrins Langford: “It’s bad enough that we have lost 60 feet in the last 10-12 years of groundwater resources where those was no diminishment for the previous 100 or so years. That’s bad enough.”

|

What’s worse, Langford says, is that no one seems to be doing the math on how long it would take to recover aquifer levels if locals ever decided to reverse the trend. Only about 5% of the rain that falls in a given year makes its way into the portion of the Trinity Aquifer near Comfort. “Well, you do the math. We’ve lost 60 feet and an average rainfall is 30 inches per year, and if it recharges at 5% that’s 1.5 inches of recharge.” For the aquifer to recover what it has lost in the last decade would take 480 years of average rainfall. “And,” Langford emphasizes, “we’re being asked to give another 30 [feet].”

In most places in Texas, the goal is for the planned depletion of the local water account.

It is not only the ranching families of the Hill Country who are being asked to give more water to satisfy limitless demand. The reliability of homeowners’ wells is also at stake—a risky proposition in a region with few alternatives for water supply. But regulation is powerless to slow the astronomical growth of groundwater production in this part of the state.

|

As of September 2014, 98% of the registered groundwater wells in Langford’s groundwater district, the Cow Creek Groundwater Conservation District, were exempt from permitting or pumping restrictions. The choice to regulate these wells is beyond the groundwater district's control—the Texas Legislature exempts all domestic wells on tracts of land greater than 10 acres from groundwater regulation, as long as they were designed to pump less than 25,000 gallons of water a day (that’s about 80% of the water an average Texan household uses each year). This means that in areas like Langford’s, most of the water use is unrestricted. From 2011-2014, about 60% of the water pumped in the Cow Creek GCD was pumped by exempted wells. (Source: State of the District – Annual Report to the Board for FY 2013-2014, Cow Creek Groundwater Conservation District, provided by Milan Michalec)

|

Only 4 out of the state’s 99 groundwater districts have set Desired Future Conditions to reflect how much groundwater can be pumped before springs and creeks start to fail.

The more ranchettes that are built, the more groundwater wells mining the Trinity, the lower the water table falls. Ironically, the streams and swimming holes that bring most newcomers to the Hill Country are the first casualty.

When the State Legislature voted on the Groundwater Management Act in 1949, its only chance of passage was in putting groundwater management in the hands of local government. For 65 years, local control has been the state’s mantra of groundwater regulation, the wisdom being that the local groundwater users who will be most affected by water pumping are the best positioned to decide how to regulate themselves. What this conventional wisdom ignores is that in many places in Texas, water is anything but local. The effects of the decisions of how much groundwater to pump in the Hill Country don’t stay in the Hill Country. This region is the point of origin for 7 rivers that water roughly a quarter of the state, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico—rivers that get most of their flow from groundwater. |

In a typical year, rivers in Texas get anywhere from 15-40% of their flow from the water below ground. During drought, this dependence on groundwater inflows increases dramatically. As our ongoing drought wore on in 2014, 80% of the water flowing past the chemical refineries in the Gulf city of Victoria came from springs in Central Texas. During drought years, the Colorado River—Austin’s only water source—receives as much as 60% of its inflow from springs in its tributaries. (source) Yet despite the strong interdependence of water above and below ground, only 4 out of the state’s 99 groundwater districts have set Desired Future Conditions to reflect how much groundwater can be pumped before springs and creeks start to fail. Perhaps, then, it should be no surprise that they are failing.

|

Virtually all of the surface water in Texas - some 80% - originates within the state.

From Langford’s perspective, the statewide drumbeat to lower groundwater tables is driven not by apathy, but by ignorance. “The folks who make all the decisions about this,” Langford says, “don’t realize that when they turn the tap on in the Capitol of Texas building that the water that comes out of that tap comes from 200 miles away. And how does it get there? It gets there from private land that feeds groundwater that nourishes springs.” Drill more wells to pump water out, pave more land to block the recharge of water into the soil, and the inevitable result will be less water for everyone.

Virtually all of the surface water in Texas—some 80%--originates within the state. (source) How private lands are managed and how much water they withdraw matters as much as how much rain we receive. |

|

If what were happening on private land within Texas were happening across a state or international border, the State of Texas would intervene on behalf of the Texans who hold claims to its rivers. It is in just such a battle now in Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado, a federal case whose merits rest on the claim that Texas' share of the Rio Grande is being taken by New Mexico's farmers' groundwater wells.

As of now, there has been no assertion of state authority to protect Texas' surface waters from the groundwater pumping of private landowners. Yet as groundwater tables fall, so will the base flow of Texas' rivers. Like most of the American West, there are more water rights entitling people to water in Texas’ rivers than there is water. How many more water rights will have to be retired once our Desired Future Conditions have been met? So far, no one is asking. To ask would be to admit that we have a problem.

As of now, there has been no assertion of state authority to protect Texas' surface waters from the groundwater pumping of private landowners. Yet as groundwater tables fall, so will the base flow of Texas' rivers. Like most of the American West, there are more water rights entitling people to water in Texas’ rivers than there is water. How many more water rights will have to be retired once our Desired Future Conditions have been met? So far, no one is asking. To ask would be to admit that we have a problem.

|

|

HOW TO MAKE A RIVER DISAPPEAR |

|

“From Elephant Butte to Presidio, the river is completely gone.” - Colin McDonald

From the bridge over the Pecos River just before it merges with the Rio Grande, you can see both rivers before their confluence. The bridge, which at first seems absurdly high (the road clears the bluffs, which themselves stand a good 250 feet above the river), looms above the remains of its predecessor below. The pylons of that bridge survived the floods of 1954, when rains from Hurricane Alice brought an 86-foot wall of water barreling down the Pecos. The bridge did not. (source)

From this vantage, the Pecos—a salty, muddy backwater that the U.S. Army decided was too poor even for the Navajos to drink - cuts a much more imposing figure than the Rio Grande, a river that connects 3 states, 2 nations and 5 million people.

Although it is still called by a single name, the Rio Grande hasn’t been a single river for more than fifty years, ever since the federal government built the Elephant Butte reservoir to conserve water for New Mexican and Texas farmers. Back in those days, when any water that was left to the fish of the stream was considered a waste, water conservation meant a very different thing than it does today. The river at Elephant Butte, the nexus of the dispute between Texas and New Mexico, wasn’t anything then like what it is today, either. When it was built, the dam’s designers added hydroelectric turbines, meant to produce energy 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Today, water only flows over the dam during growing season, which itself has been shrinking with each passing decade. In 2014, there was enough water for 8 weeks of flow, in 2013, only 6 weeks.

From this vantage, the Pecos—a salty, muddy backwater that the U.S. Army decided was too poor even for the Navajos to drink - cuts a much more imposing figure than the Rio Grande, a river that connects 3 states, 2 nations and 5 million people.

Although it is still called by a single name, the Rio Grande hasn’t been a single river for more than fifty years, ever since the federal government built the Elephant Butte reservoir to conserve water for New Mexican and Texas farmers. Back in those days, when any water that was left to the fish of the stream was considered a waste, water conservation meant a very different thing than it does today. The river at Elephant Butte, the nexus of the dispute between Texas and New Mexico, wasn’t anything then like what it is today, either. When it was built, the dam’s designers added hydroelectric turbines, meant to produce energy 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Today, water only flows over the dam during growing season, which itself has been shrinking with each passing decade. In 2014, there was enough water for 8 weeks of flow, in 2013, only 6 weeks.

|

El Paso claims the water delivered downstream from Elephant Butte. Then there is no river, not for 300 miles. This forgotten stretch of river was the most surreal for Colin McDonald, who last year traversed the Rio Grande along its entire 1,900 miles in his Disappearing Rio Grande Expedition. “From Elephant Butte to Presidio, the river is completely gone,” says McDonald; in El Paso, every drop of water is diverted, the river straightened and channeled, “everything short of putting it into a pipe, which El Paso has proposed several times.” Not even the city’s wastewater effluent makes it back to the river—that goes to farms too.

Human engineering has permanently changed the natural plumbing of the river. Farmers once pumped groundwater to dispose of it in the river, saving their crops’ roots from the salt of the soil. As the groundwater table fell, so did the land itself; now the riverbed is like a reverse levee, higher in many points than the farmland around it. |

The relationship between the Rio Grande and the Hueco Bolson Aquifer below it has inverted. Where the aquifer once created baseflow in the Rio Grande, the river has now become a losing stream, pouring its water into the earth. Six times as much water from the Rio Grande now escapes underground as the aquifer ever gave to it.

On the 300-mile Forgotten Reach from Ft Quitman to Presidio, McDonald walked the riverbed more than he paddled. An occasional trickle of water—an old oil and gas well that had hit a hot spring vein near Candelaria—would merit blowing up his inflatable kayak, but for the most part, the river was as much a memory as the ancient riverbeds you see flying over the Mojave. The earth remembers them, but hardly anyone else.

On the 300-mile Forgotten Reach from Ft Quitman to Presidio, McDonald walked the riverbed more than he paddled. An occasional trickle of water—an old oil and gas well that had hit a hot spring vein near Candelaria—would merit blowing up his inflatable kayak, but for the most part, the river was as much a memory as the ancient riverbeds you see flying over the Mojave. The earth remembers them, but hardly anyone else.

|

"If we want the Devils River to continue flowing, we have to figure out what’s happening to this place that is bigger than most states." - Colin McDonald

|

The Rio Grande known to Texans outside of El Paso is no longer connected to the river that flows from Colorado; we have created two distinct rivers through our pumping, damming and diversions. The Lower Rio Grande is formed by the inflows of Mexico’s Rio Conchos, more than 300 miles downstream of El Paso. This is the iconic Rio Grande that lives in the minds of most Texans, the river that passes by the whiskey-soaked ghost mine of Terlingua and under the red bluffs of Santa Elena Canyon in Big Bend National Park.

That part of the river, McDonald says, is its most beautiful by far. “The beauty of the lower canyons and the remoteness and wilderness of the wild and scenic reach from Big Bend National Park to Amistad is, hands down, the most gorgeous reach of the river that I’ve seen,” he told me over the phone while still 500 miles from the river’s end. “There’s no power lines over it; for the vast majority of it you don’t even hear airplanes. There’s a couple of houses toward the end of it, but when you see a guy riding on a horse, he’s about as real a cowboy as you’re going to meet. He’s going to go round up 3 cows for every sector [64 acres]. It’s a very wild, very rough place. [But] it’s a ridiculously accessible part of the river. The river is so gentle, it’s lovely.” From the federally-designated Wild and Scenic reach of the Rio Grande, it might be possible to forget that we have broken this river, and that we may be racing toward shattering what remains of it. The reason why, McDonald says, can be summed up this way: “We have 19th century water laws, 20th century infrastructure and 21st century problems.”

After the Rio Grande is revived by the Rio Conchos, it receives its last infusion of life another two hundred miles downstream, in a desert oasis called Val Verde County. A third of the inflows to the Lower Rio Grande come from Val Verde, which--despite its location on the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert--has an abundance of water, most of it provided by the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer. |

Now that last injection of freshwater into the Lower Rio Grande has found yet another source of competition: groundwater marketers. Val Verde is a so-called “white area” on the map of groundwater regulation, a place with no regulatory limits on pumping. If someone were to sign a contract for the more than 50 billion gallons a year that groundwater marketers say can be produced from Val Verde County, that water would no longer make it to the Rio Grande.

Val Verde's abundance depends on the ready import of rainfall from counties on the Edwards Plateau to the northeast, and the steady export of groundwater in the consistent flow of Val Verde’s springs, some of which count among the largest in Texas. While much of the county’s 2 million acres are dry scrubland, the places where the Edwards-Trinity springs to the surface are lush, the Caribbean blue water as perfect as you can imagine.

One of these is the near-mythic Devils River, which until a decade ago was braved only by the truly intrepid paddler willing to endure (and sometimes exchange) gunfire with protective landowners. Today, the Devils is more accessible than ever before, with one 20,000-acre State Natural Area near Dolan Falls and another planned to open further downriver. Theoretically, the river is more protected than ever before as well: alongside the state's investment, The Nature Conservancy holds conservation easement or title to another 160,000 acres.

But, says McDonald, it is not so easy to protect the Devils. “Everybody recognizes it’s an amazing place. Dolan Falls is pretty, so you put a fence around it. Okay, that’s protecting the physical surface, but if we want the Devils River to continue flowing, we have to figure out what’s happening to this place that is bigger than most states." Without inflows from the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer, there is no Devils River. Without the Devils River, there is 260,000 acre-feet less water flowing into the Rio Grande's reservoirs for delivery to the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

Val Verde's abundance depends on the ready import of rainfall from counties on the Edwards Plateau to the northeast, and the steady export of groundwater in the consistent flow of Val Verde’s springs, some of which count among the largest in Texas. While much of the county’s 2 million acres are dry scrubland, the places where the Edwards-Trinity springs to the surface are lush, the Caribbean blue water as perfect as you can imagine.

One of these is the near-mythic Devils River, which until a decade ago was braved only by the truly intrepid paddler willing to endure (and sometimes exchange) gunfire with protective landowners. Today, the Devils is more accessible than ever before, with one 20,000-acre State Natural Area near Dolan Falls and another planned to open further downriver. Theoretically, the river is more protected than ever before as well: alongside the state's investment, The Nature Conservancy holds conservation easement or title to another 160,000 acres.

But, says McDonald, it is not so easy to protect the Devils. “Everybody recognizes it’s an amazing place. Dolan Falls is pretty, so you put a fence around it. Okay, that’s protecting the physical surface, but if we want the Devils River to continue flowing, we have to figure out what’s happening to this place that is bigger than most states." Without inflows from the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer, there is no Devils River. Without the Devils River, there is 260,000 acre-feet less water flowing into the Rio Grande's reservoirs for delivery to the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

The Valley needs all the water it can get. For the better part of a decade, this agricultural economy—the seat of Texas’ citrus production, the third largest in the United States—has been in a water deficit, as drought in Mexico has reduced inflows on the Rio Conchos.

In the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the water deficit is obvious. Irrigation canals channel the Rio Grande’s water across the farms that grow Texas’ grapefruit, lemon and orange crops to the border cities whose populations have exploded in recent decades. Demand for water in the Valley is already exceeding supply on the Rio Grande, an imbalance driven to a head by the drought that started in 2009. By spring of 2013, cities panicked as they realized there might not be enough “push water” to move their allocation of the Rio Grande through the irrigation canals to their water treatment plants.

In the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the water deficit is obvious. Irrigation canals channel the Rio Grande’s water across the farms that grow Texas’ grapefruit, lemon and orange crops to the border cities whose populations have exploded in recent decades. Demand for water in the Valley is already exceeding supply on the Rio Grande, an imbalance driven to a head by the drought that started in 2009. By spring of 2013, cities panicked as they realized there might not be enough “push water” to move their allocation of the Rio Grande through the irrigation canals to their water treatment plants.

With the specter of more than a million Texans running short of water, the state’s Congressional delegation has pushed the State Department to employ whatever tools are necessary to force Mexico to make up its arrears to Texas, leading to much chest beating in the halls of Congress and the media. But, McDonald says, “the Rio Conchos thing about Mexico not delivering water? The farmers across the valley in Mexico from the farmers in South Texas, they’re being screwed twice as much as the farmers in Texas.” For every acre-foot of water on the Rio Grande that Mexico owes Texas under the Treaty of 1944, Mexico owes twice that much to its own farmers further downstream, where deliveries on their side of the border in the Lower Rio Grande Valley have been reduced as well. “For every acre-foot Texas thinks it’s not getting, there’s 2 acre-feet that Mexico’s not getting. Envision the Valley—the exact same thing is going on on the other side of the river. There’s oil and gas exploration, there’s grapefruits and vegetables and cotton and alfalfa grown in Mexico.”

The 1944 Treaty entitles Texas to all the water its tributaries contribute to the Rio Grande--tributaries like those in Val Verde County. But while it continues to fight its neighbors for the water to which it is entitled, under the banner of local control, it has done nothing to protect its share of water from the aspirations of groundwater producers in Texas.

Under the laws of the State of Texas, the people of the Valley may hold rights to the Rio Grande, but they have no right to the source of a third of that water: the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer. The right to that groundwater rests exclusively with the landowners above the aquifer, who can pump, pipe and sell as much as they wish to whomever they choose.

The 1944 Treaty entitles Texas to all the water its tributaries contribute to the Rio Grande--tributaries like those in Val Verde County. But while it continues to fight its neighbors for the water to which it is entitled, under the banner of local control, it has done nothing to protect its share of water from the aspirations of groundwater producers in Texas.

Under the laws of the State of Texas, the people of the Valley may hold rights to the Rio Grande, but they have no right to the source of a third of that water: the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer. The right to that groundwater rests exclusively with the landowners above the aquifer, who can pump, pipe and sell as much as they wish to whomever they choose.

|

McDonald’s time on the Rio Grande demonstrated to him that “there’s no free water—if you take water from anywhere that’s hydrologically upstream from the Valley, you’re taking that water from the Valley.” Yet water users in the Lower Rio Grande are only just starting to organize in response to this new threat. “If I was a farmer in the Valley I’d have a lot of things on my worry list that would come first. It’s part of this general process of realizing, shit, rivers are big, complicated systems that we have to look at as a whole. Right now we like to work on dividing them up.”

I had the chance to join McDonald on the last day of his 6-month voyage down the Rio Grande. It was a bitter January day, even in the temperate Valley. Neither my tentmates nor I slept much the night before, listening to the wind tear at the trees and cables, and hoping it would die down by morning. At launch, wind gusts of 40 miles per hour churned up the water. It was the first time McDonald had seen whitecaps on the Rio Grande, and he assured us these were the worst paddling conditions of his 1,900-mile trip. Some strange mercy visited us on the river that day. The wind hardly let up. But somehow, whatever direction we turned, it remained mostly at our backs. Few people greeted us on the 13-mile paddle. Bales of snarled monofilament line marked a Mexican fishing camp, and the fishermen setting their lines waved to us in their seafoam green Mackintoshes. The landscape changed in subtle increments as we approached the Gulf, first from grasses to mangroves sheltering blue herons and snowy egrets, and, finally, to dunes. Waves crashed over the thin spit of sand sheltering the river’s mouth from the Gulf. |

On our last mile, the winds shifted to our face, and the group fell silent. Our boat, which had swung wildly in the shifting winds, now barely moved ahead at all. This was, I realized, just a taste of what McDonald had tolerated for six months on his forgotten river. Six months of solitary beauty; six months of sodden feet and lonely nights with only the real or imagined sounds of human coyotes for company. I couldn’t understand how he did it, but when we reached that sandy spit, I understood why.

Barely onshore, McDonald abandoned his canoe for an ocean kayak, paddling into the breakers. There, the wind and the water buffeting him, McDonald uncorked the vial of snowmelt he had collected on the Colorado mountain where the river began its journey, and reunited it with the Gulf. It was the first time in nearly a hundred years that the Rio Grande had completed its course from snow to sea.

Barely onshore, McDonald abandoned his canoe for an ocean kayak, paddling into the breakers. There, the wind and the water buffeting him, McDonald uncorked the vial of snowmelt he had collected on the Colorado mountain where the river began its journey, and reunited it with the Gulf. It was the first time in nearly a hundred years that the Rio Grande had completed its course from snow to sea.

|

|

SOMETHING CALLED 'SOLVE THE PROBLEM' |

|

Over the next 50 years the state’s population is projected to double—a daunting proposition in light of the water shortages we’re already experiencing. All over the state, people are looking for more water. Can we produce as much water as we need without draining the land dry?

Few things are more complex than managing water. Yet the solution is, at its heart, elegant in its simplicity. Texans can rely only on each other to keep water flowing. We must collaborate, and we must do it in ways that sometimes may feel incredibly risky.

In some ways, it is not that different from cave diving. “Alright, you know cave diving, we have an immense amount of training, we have a ridiculous amount of equipment, we try to use prudence in our dive planning,” Gregg Tatum explained as his partner, David Moore, tested air tanks. “Even when everything is planned to the nth degree, you can still have equipment failures…you learn to do something called ‘Solve The Problem.’” The trust he has built in his equipment, his training and his dive partner, Tatum says, is why he could be in a West Texas spring 225 feet underwater, his buoyancy compensator torn, his gas cylinder completely depleted, and still have time to think, "this is really a cool place, I really enjoy being here. When you rely on your training and you think through the problem, you’re going to be alright.”

Our problems in Texas aren’t impossible to solve. But if we’re going to solve them, we have to connect the thread between the waters that move below ground and those that wind above. We have to give Texans legal footing to work together to preserve the waters they share. And we have to build trust among the ranchers and orange growers, the cities and shrimpers whose destinies are bound together by water.

Few things are more complex than managing water. Yet the solution is, at its heart, elegant in its simplicity. Texans can rely only on each other to keep water flowing. We must collaborate, and we must do it in ways that sometimes may feel incredibly risky.

In some ways, it is not that different from cave diving. “Alright, you know cave diving, we have an immense amount of training, we have a ridiculous amount of equipment, we try to use prudence in our dive planning,” Gregg Tatum explained as his partner, David Moore, tested air tanks. “Even when everything is planned to the nth degree, you can still have equipment failures…you learn to do something called ‘Solve The Problem.’” The trust he has built in his equipment, his training and his dive partner, Tatum says, is why he could be in a West Texas spring 225 feet underwater, his buoyancy compensator torn, his gas cylinder completely depleted, and still have time to think, "this is really a cool place, I really enjoy being here. When you rely on your training and you think through the problem, you’re going to be alright.”

Our problems in Texas aren’t impossible to solve. But if we’re going to solve them, we have to connect the thread between the waters that move below ground and those that wind above. We have to give Texans legal footing to work together to preserve the waters they share. And we have to build trust among the ranchers and orange growers, the cities and shrimpers whose destinies are bound together by water.